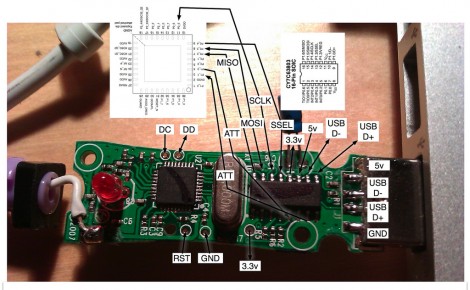

[calculon] was able to modify a “dumb” adapter to allow his Canon SLR to use the aperture and focus on a retro lens. With his new flip mounted wide angle lens he was able to achieve some pretty neat macro shots. By cutting away some of the cheaper ring he was able to feed the wire through and glue it onto the the cameras contact points. The wire was then attached to the inputs on the “new” lens. With a new adapter running about $375 not only was this a neat little hack but it was also a money saver. You can see some more of his photos on his flicker