Here’s an interesting experiment that attempts to measure the quality of a linear rail by using a form of visual odometry, accomplished by mounting a camera on the rail and analyzing the video with open-source software usually used to stabilize shaky video footage. No linear rail is perfect, and it should be possible to measure the degree of imperfection by recording video footage while the camera moves down the length of the rail, and analyzing the result. Imperfections in the rail should cause the video to sway a proportional amount, which would allow one to characterize the rail’s quality.

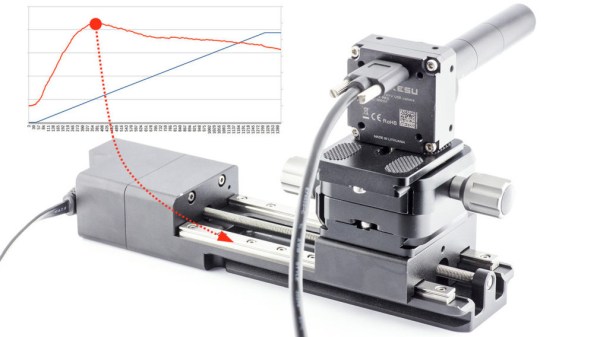

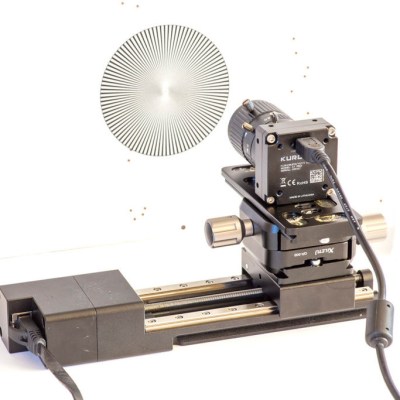

To test this idea, [Saulius] attached a high-definition camera to a linear rail, pointed the camera towards a high-contrast textured pattern (making the resulting video easier to analyze), and recorded video while moving the camera across the rail at a fixed speed. The resulting video gets fed into the Deshaker plugin for VirtualDub, of which the important part is the

To test this idea, [Saulius] attached a high-definition camera to a linear rail, pointed the camera towards a high-contrast textured pattern (making the resulting video easier to analyze), and recorded video while moving the camera across the rail at a fixed speed. The resulting video gets fed into the Deshaker plugin for VirtualDub, of which the important part is the deshaker.log file, which contains X, Y, rotate, and zoom correction values required to stabilize the video. [Saulius] used these values to create a graph characterizing the linear rail’s quality.

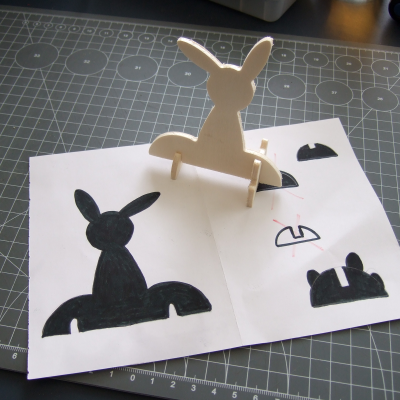

It’s a clever proof of concept, especially in how it uses no special tools and leverages a video stabilizing algorithm in an unusual way. However, the results aren’t exactly easy to turn into concrete, real-world measurements. Turning image results into micrometers is a matter of counting pixels, and for this task video stabilizing is an imperfect tool, since the algorithm prioritizes visual results instead of absolute measurements. Still, it’s an interesting experiment, and perfectly capable of measuring rail quality in a relative sense. Can’t help but be a bit curious about how it would profile something like these cardboard CNC modules.