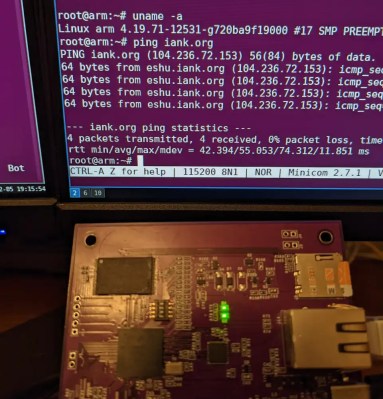

Out of all the laptop upgrade options typically available, you wouldn’t expect this specific one. [controlmypad] decided to take a part of his RS485 device programming workflow and put it inside of a spare laptop he picked up for cheap. Typically, he’d occupy some desk space and lay out an unwieldy combination of a USB-RS485 dongle, a PoE power injector, a PSU for that injector, and a few cables to join it all – being extra weight in the tool bag, cluttering the workspace when laid out, and the RS485 adapter slowly wearing out the USB ports during the work-related motions. No reason that all of this couldn’t be packed inside a laptop, however.

What helps a lot is that, in many modern cheap laptops, the motherboard is fairly small, and the DVD drive plastic placeholder can be omitted without second thought. Cutting off the plastic molding from both of the adapters turns them into a nicely reusable circuit board and a small PoE module, respectively. After laborious yet careful cutting of the laptop case with a hobby knife, the PoE injector fits right in and, essentially, adds an extra RJ45 port to the laptop. From where the Hackaday.io write-up left off, it doesn’t seem like this mod got fully completed, but most of the important details are there for us to learn from. What got left out is connecting it to an internal USB port (should help that the motherboard’s schematics are available online), as well as creating 12V-24V from the laptop’s power rails. At this point, however, this mod is a big step forward usability-wise, even if it still requires an external PSU.

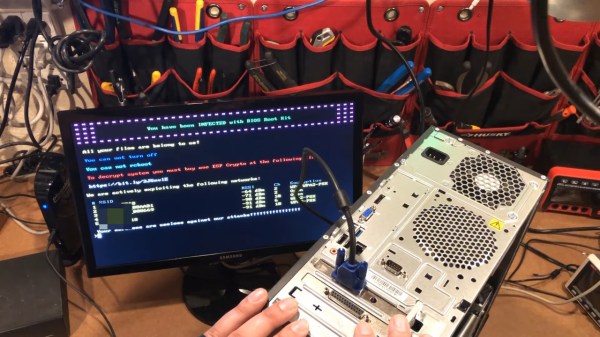

Laptop internal upgrade projects are rare but cherished – it’s a combination of “daring”, “inquisitive” and “meticulous” that results in people successfully hacking on a thing they certainly were not meant to hack, and have that thing serve their needs better. Apart from all the EEE PC upgrade options that set the bar for a generation of laptop modders, there’s a myriad of unconventional laptop modification vectors – you could do a thorough from-scratch Type-C charging port conversion, replace your webcam with an FSF-endorsed open firmware WiFi dongle, build in a “12-axis” sensor for auto-orientation and data-logging, or invent a remote self-destruct mechanism for your laptop. Those are, indeed, quite a few things you won’t typically find in the list of available options while customizing your laptop at the manufacturer website.