The MOS Technology 6502 is a microprocessor which casts a long shadow over the world of computing. Many of you will know it as the beating heart of so many famous 8-bit machines from the likes of Commodore, Apple, Acorn, and more, and it has retained enough success for a version to remain in production today. It’s still a surprise though, to note that this part is now fifty years old. Though there are several contenders for its birthday, the first adverts for it were in print by July 1975, and the first customers bought their chips in September of that year. It’s thus only fitting that in August 2025, we give this processor a retrospective.

The Moment Motorola Never Really Recovered From

The story of the 6502’s conception is a fascinating tale of how the giants of the early mocroprocessor industry set about grappling with these new machines. In the earlier half of the 1970s, Chuck Peddle worked for Motorola, whose 6800 microprocessor reached the market in 1974. The 6800 was for its time complex, expensive, and difficult to manufacture, and Peddle’s response to this was a far simpler device with a slimmed-down instruction set that his contact with customers had convinced him the market was looking for: the 6502.

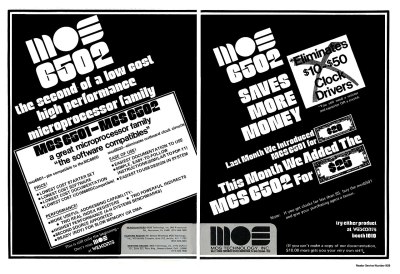

There’s a tale of Motorola officially ordering him to stop working on this idea, something he would later assert as such an abandonment of the technology that he could claim the IP for himself. Accompanied by a group of his Motorola 6800 colleagues, in the summer of 1974 he jumped ship for MOS Technology to pursue the design. What first emerged was the 6501, a chip pin-compatible with the 6800, followed soon after by the 6502, with the same core, but with an on-board clock oscillator. Continue reading “Happy Birthday 6502”