A while back our good buddy [Ch00f] built a QR code clock, unreadable to both humans and computers. A human couldn’t read the clock because of the digital nature of a QR code, and because the clock used persistence of vision in driving the LEDs, a digital camera can’t capture all the pixels in the QR code at the same time. It’s a highly useless but impressive art piece. Now, [Ch00f] is turning that build on its head. He created a rudimentary display that is invisible to the human eye, but easily detected with a digital camera.

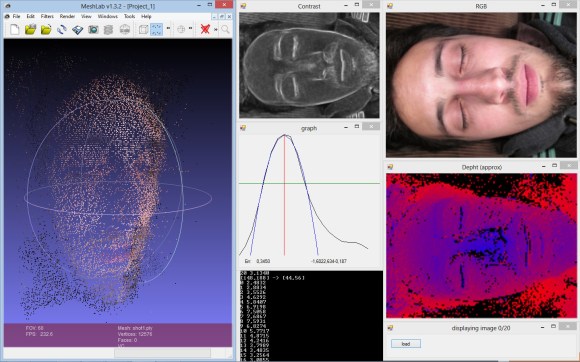

This build exploits a basic property of CMOS digital cameras – the rolling shutter. Because it takes time to get pixels off a modern digital image sensor, each picture is actual a composite of many different strips, each taken slightly out of sequence. You can see this for yourself by taking a picture of something rotating very fast with your camera phone; a picture of an airplane propeller will make the blades appear curved, or look like [Dr. Seuss] has an aeronautical engineering degree.

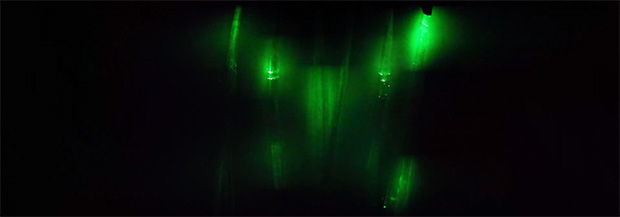

To create his display, [Ch00f] found a few inexpensive fiber optic lights. By aligning a few of these into columns and lighting them up in a precise sequence, he can exploit the rolling shutter and make an image appear. To the human eye, it looks like a solid wall of illuminated fiber optics.

As for how practical this build is, [Ch00f] says not much. For cell phone cameras, you’d need to have a very, very short exposure time for this to work. The only way to do that is to make this display unbelievably bright, or just put it out in the sun. We can’t see that being practical for any potential use case, but we’d be more than happy to see a large-scale attempt at displaying images with this technique.