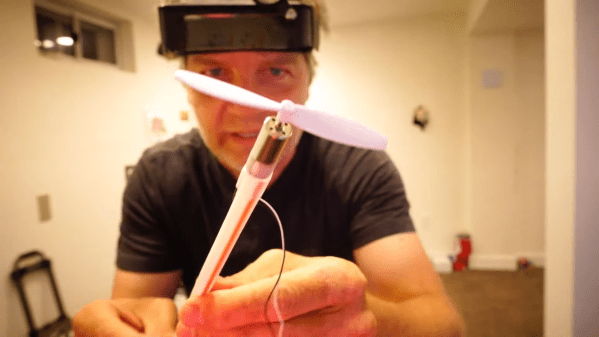

For a long time radial aircraft engines, with their distinctive cylinder housings arranged in a circle, were a common sight on aircraft. As an experiment, [KendinYap], wanted to see if he could combine 3 small DC motors into a usable RC aircraft motor, effectively creating an electric radial engine.

The assembly consists of three “180” type brushed DC motors, mounted radially in a 3D printed casing. A 3D printed conical gear is attached to each motor shaft, which drives a single output gear and shaft mounted in the center with two bearings. The gear ratio is 3:1. A variety of propellers can be mounted using 3D printed adaptors. As a baseline, [KendinYap] tested a single motor on a scale with a 4.25-inch propeller on a scale, which produced 170 g of thrust at 21500 RPM. Once integrated into the engine housing, the three motors produced 490 g of thrust at 5700 RPM, with a larger propeller. Three independent motors and propellers should theoretically provide 510 g of thrust, so there are some mechanical losses when combining 3 of them in a single assembly. However, it should still be capable of powering a small RC plane. It’s also not impossible that a different propeller could yield better results.

While there is no doubt that it’s no match for a brushless RC motor, testing random ideas just to see if it’s possible is usually fun and an excellent learning experience. We’ve seen some crazy flyable RC power plants, including a cordless drill, a squirrel-cage blower, and a leaf blower.