It’s not infrequent that we see the combination of moisture sensors and water pumps to automate plant maintenance. Each one has a unique take on the idea, though, and solves problems in ways that could be useful for other applications as well. [Emiliano Valencia] approached the project with a few notable technologies worth gleaning, and did a nice writeup of his “Autonomous Solar Powered Irrigation Monitoring Station” (named Steve Waters as less of a mouthful).

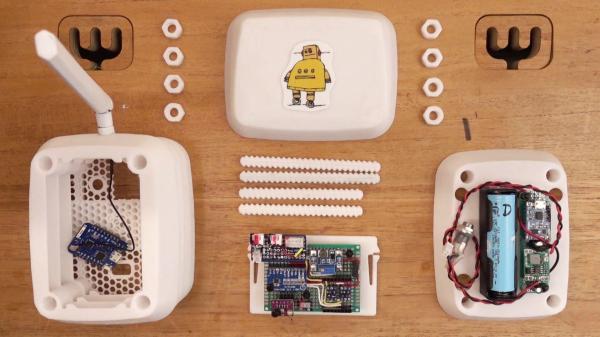

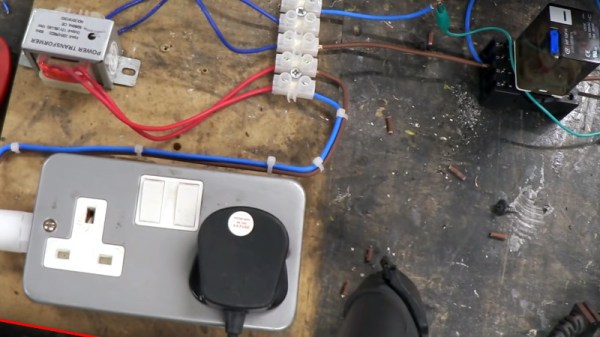

Of particular interest was [Emiliano]’s solution for 3D printing a threaded rod; lay it flat and shave off the top and bottom. You didn’t need the whole thread anyway, did you? Despite the relatively limited number of GPIO pins on the ESP8266, the station has three analog sensors via an ADS1115 ADC to I2C, a BME280 for temperature, pressure, and humidity (also on the I2C bus), and two MOSFETs for controlling valves. For power, a solar cell on top of the enclosure charges an 18650 cell. Communication over wireless goes to Thingspeak, where a nice dashboard displays everything you could want. The whole idea of the Stevenson Screen is clever as well, and while this one is 3D printed, it seems any kind of stacking container could be modified to serve the same purpose and achieve any size by stacking more units. We’re skeptical about bugs getting in the electronics, though.

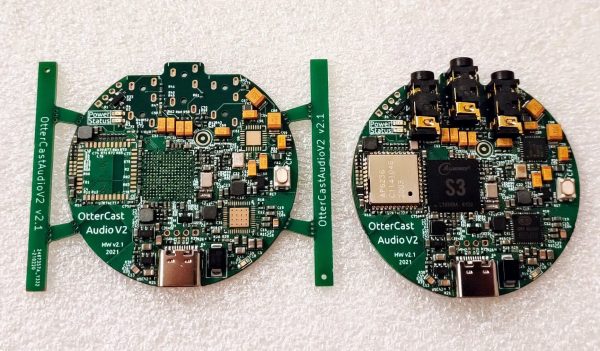

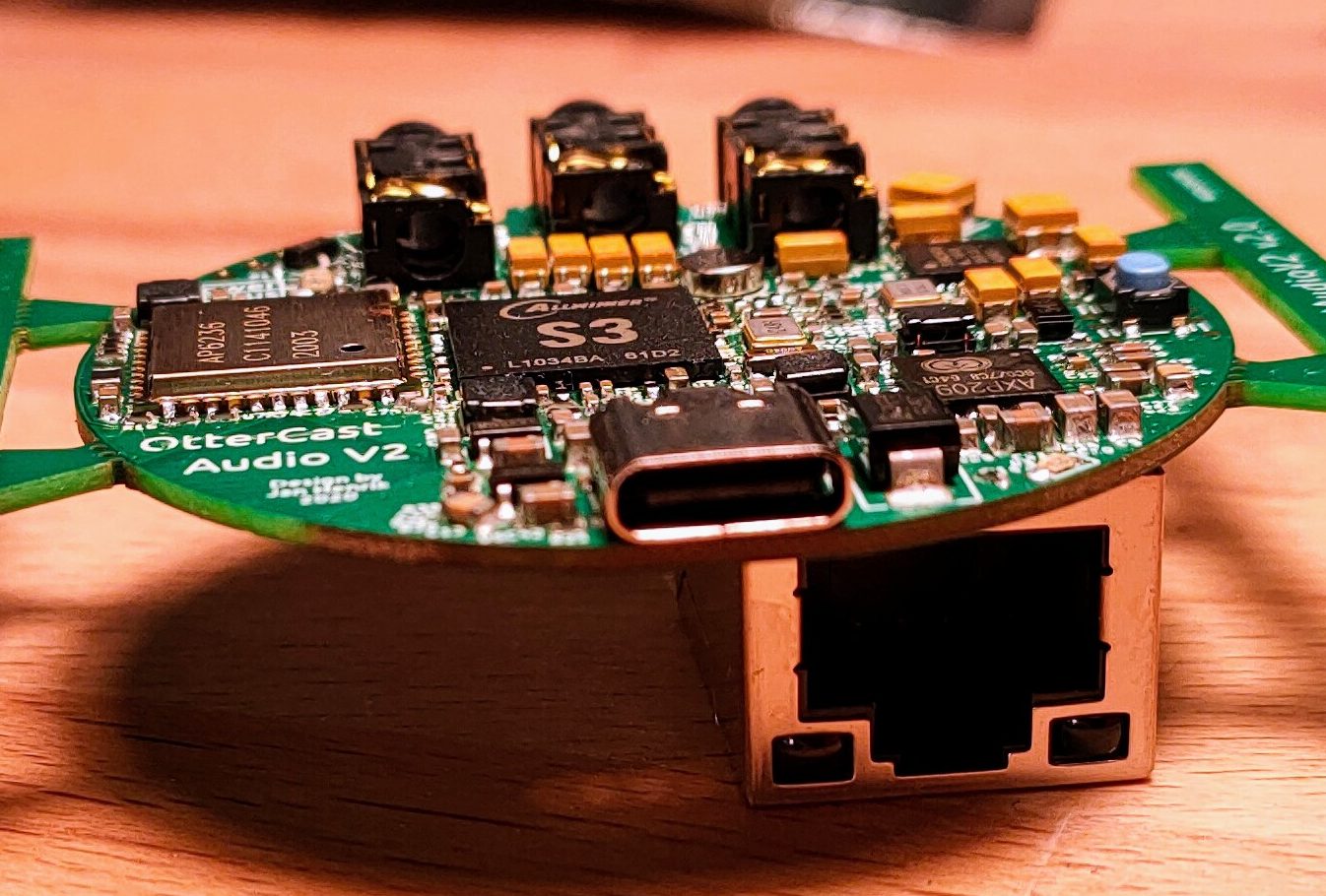

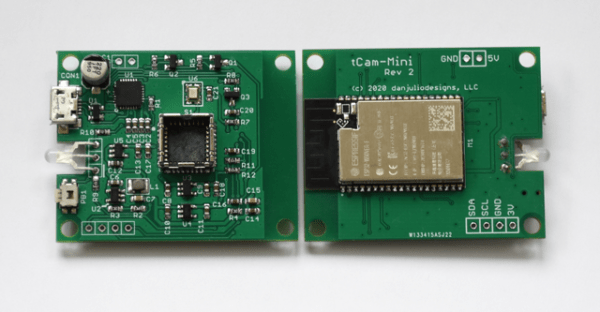

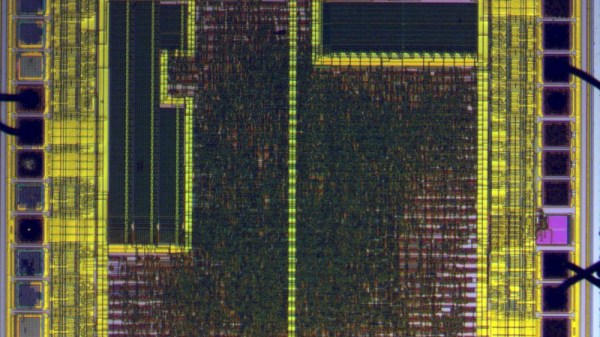

We recently saw an ESP32-based capacitive moisture sensor on a single PCB sending via MQTT, and we’ve seen [Emiliano] produce other high quality content etching PCBs with a vinyl cutter.