Don’t you hate it when making your DIY X-ray machine you make an uncomfortable amount of ozone gas? No? Well [Hyperspace Pirate] did, which made him come up with an interesting idea. While creating a high voltage supply for his very own X-ray machine, the high voltage corona discharge produced a very large amount of ozone. However, normally ozone is produced using lower voltage, smaller gaps, and large surface areas. Naturally, this led [Hyperspace Pirate] to investigate if a higher voltage method is effective at producing ozone.

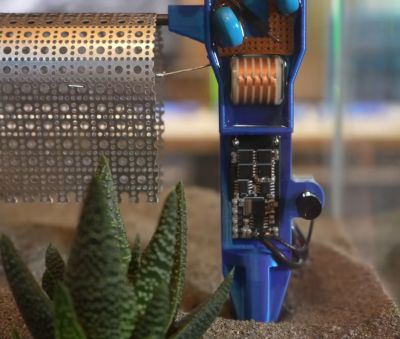

Using a custom 150kV converter, [Hyperspace Pirate] was able to test the large gap method compared to the lower voltage method (dielectric barrier discharge). An ammonia reaction with the ozone allowed our space buccaneer to test which method was able to produce more ozone, as well as some variations of the designs.