Home automation is a fine goal but typically remains confined to lights, blinds, and other things that are relatively stationary and/or electrical in nature. There is a challenge there to be certain, but to really step up your home automation game you’ll need to think outside the box. This automated garbage can that can take itself out, for example, has all the home automation street cred you’d ever need.

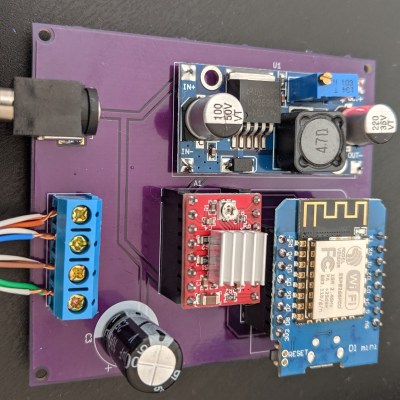

The garbage can moves itself by means of a scooter wheel which has a hub motor inside and is powered by a lithium battery, but the real genius of this project is the electronics controlling everything. A Raspberry Pi Zero W is at the center of the build which controls the motor via a driver board and also receives instructions on when to wheel the garbage can out to the curb from an Nvidia Jetson board. That board is needed because the creator, [Ahad Cove], didn’t want to be bothered to tell his garbage can to take itself out or even schedule it. He instead used machine learning to detect when the garbage truck was headed down the street and instruct the garbage can to roll itself out then.

The only other thing to tie this build together was to get the garage door to open automatically for the garbage can. Luckily, [Ahad]’s garage door opener was already equipped with WiFi and had an available app, unbeknownst to him, which made this a surprisingly easy part of the build. If you have a more rudimentary garage door opener, though, there are plenty of options available to get it on the internets.