This was gonna happen – sooner or later. [matthewhallberg] built a “Smart” trash can that is connected to the Internet and can be controlled by its own Android App. We’re not sure if the world needs it, but he wanted one and so built it. He started it out on a serious note, but quickly realized the fun part of this build – check out his funny Infomercial style video after the break.

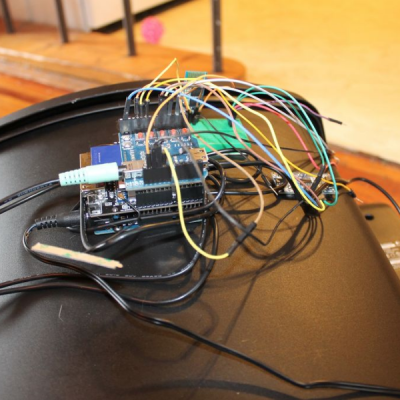

The build itself is uncomplicated and can be replicated with ease. A servo motor helps flip the lid open and close. This is triggered by an ultrasonic ping sensor, which responds when someone waves a hand in front of the trash can. A second ping sensor helps inform the user when it is full and needs to be emptied. A Leonardo with the Idunio Yun shield helps connect the trash can to the internet. An mp3 shield connected to a set of powered computer speakers adds voice capability to the trash can, allowing it to play back pre-recorded sound clips. Finally, a Bluetooth module lets him connect it to an Android phone and the companion app controls the trash can remotely.

The build itself is uncomplicated and can be replicated with ease. A servo motor helps flip the lid open and close. This is triggered by an ultrasonic ping sensor, which responds when someone waves a hand in front of the trash can. A second ping sensor helps inform the user when it is full and needs to be emptied. A Leonardo with the Idunio Yun shield helps connect the trash can to the internet. An mp3 shield connected to a set of powered computer speakers adds voice capability to the trash can, allowing it to play back pre-recorded sound clips. Finally, a Bluetooth module lets him connect it to an Android phone and the companion app controls the trash can remotely.

For the IoT side of things, [matthewhallberg] uses a Temboo account to send an email to the user when the trash can is full. The Arduino sketch, a header file to configure the Temboo account, and the Android application can all be downloaded from his blog. If this project inspires you, try building this awesome Robotic trash can which catches anything that you throw near it or read the barcodes off the trash being thrown out and update the grocery list.