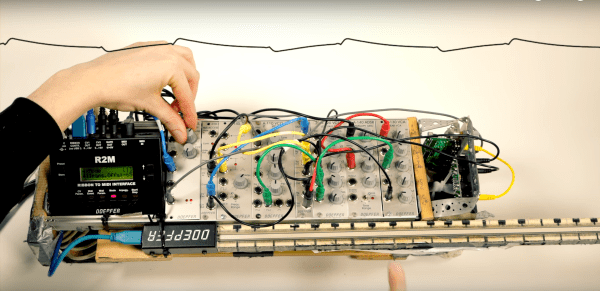

Over on YouTube, [GumpherDM3] built one of the greatest musical projects we’ve seen in a long time. It’s an analog synthesizer that is one of a kind. It’s going to stay one of a kind, too: no one would ever want to copy this mess of wires and perfboard that was successfully turned into a complete musical instrument.

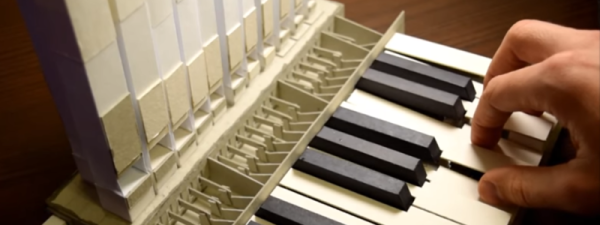

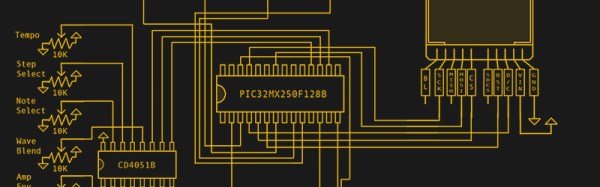

The design of this synth is what you would expect from something that draws its inspiration from semimodular synths such as the Minimoog and Korg MS20. There are four VCOs on this synth, two audio and two used for the LFOs. A four-pole low pass filter, VCA, and two envelope generators round out the purely analog portion of the build. There’s an arpeggiator in there too, which makes for a really great demo video (below).

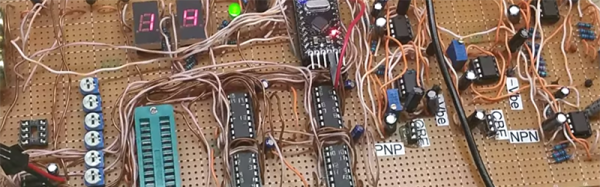

Inside, this is a true analog synth with the VCOs, filter, and VCA built around the LM13700 transconductance amplifier. The build log shows these chips spread out around half a dozen breadboards before being plugged into sockets soldered to handwired perf board. This synth is a one of a kind instrument – no one would want to build this thing twice.

Additional features include an Arduino with a MIDI in port sending out CV signals to the analog part of the synth. This thing has everything you would expect from a modern take on an analog synthesizer, and it sounds good, too.

Continue reading “A Mess Of Wires Turned Into An Analog Synth”