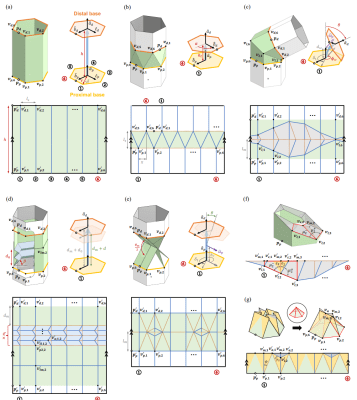

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have just published a paper on creating modular tubular origami machines which they call “Kinegami”, a portmanteau of “kinematic” and “origami”.

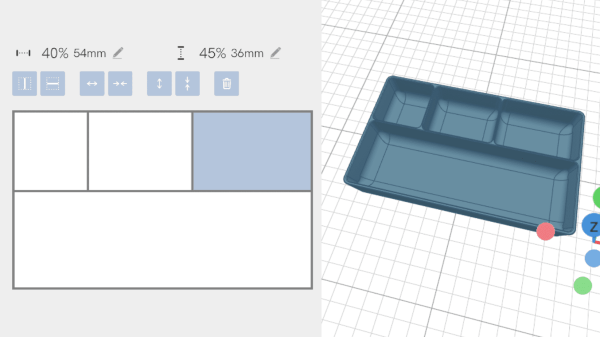

The idea behind their work is to create individual modules and joint mechanisms that can then be chained together to create a larger “serial” robot. Some example joints they propose are “prismatic” joints, allowing for linear motion, and “revolute” joints, which allow for rotational motion. One of the more exciting aspects of this process is that the joint mechanisms are origami-like structures which can be constructed from a single piece of flat material which is folded and glued together to make the module. Of particular interest is that the crease pattern for the origami-like folds can be laser cut into a material, cardboard or thin acrylic for example, which can be used as a guide to create the resulting structure. The crease patterns for the supporting structures, such as tubes or joints, can be taken from pre-formatted patterns or customized, so this method is very accessible to the hobbyist and could allow for a rich new method of rapid project prototyping.

The researchers go on to discuss how to create the composition of modules from a specification of joints and links (from a “Denavit-Hartenberg” specification) to attaching the junctures together while respecting curvature constraints (via the “Dubins path”). Their paper offers the gritty details along with the available accompanying source files. Origami hacking is a favorite subject of ours and we’ve featured articles on the use of origami in medical technology to creating inflatable actuators.

Video after the break!