Sometimes antennas can seem like black magic. However, when you see things like a dish antenna, it sort of makes sense, right? Just like a mirror focuses light, the parabola of a dish focuses RF energy. But [IMSAI Guy] shows another common-sense antenna arrangement: a corner reflector dipole. He had built one years ago and decided to do a bit of research and make another one.

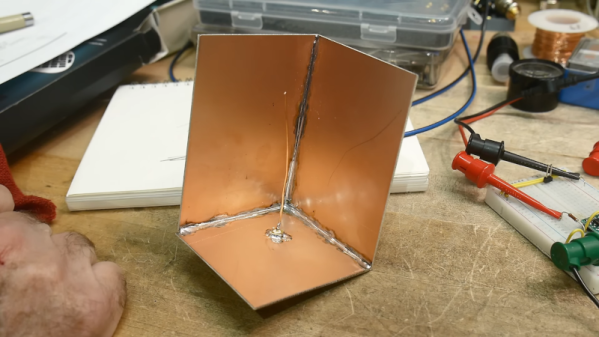

In a clever use of copper-clad board, he was able to make a reasonable reflector by soldering together three boards and an RF connector. A single wire makes the “driven element,” and by bending it to just the right position, you can change the characteristic impedance for matching.

The antenna, in this case, is essentially a quarter-wave antenna with a ground plane and reflector arrangement. After the obligatory chalk talk, he breaks out the vector network analyzer and shows how well it matches. He didn’t, however, measure the gain or directional selectivity due to the reflector.

Intuitively, you’d think this kind of antenna would be good for direction finding purposes. In fact, hams that use handy talkies for direction finding often use their bodies to block signals, much like these reflectors should.

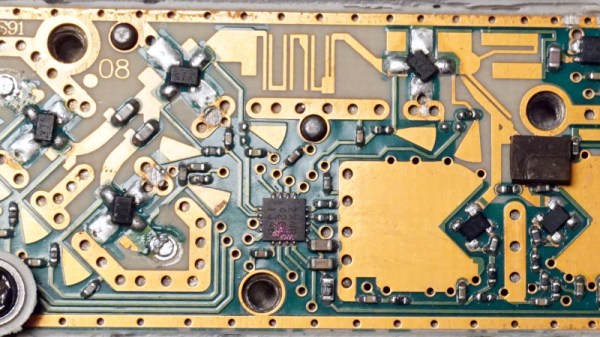

The [IMSAI Guy] reflector is pretty small, but you can easily make bigger ones. Using PCB material for antennas isn’t anything new, either, but we still enjoyed this simple corner reflector build.