When your homebrew Yagi antenna only sort-of works, or when your WiFi cantenna seems moody on rainy days, we can assure you: it is not only you. You can stop doubting yourself once and for all after you’ve watched the Tech 101: Antennas webinar by [Dr. Jonathan Chisum].

[Jonathan] breaks it all down in a way that makes you want to rip out your old antenna and start fresh. It goes further than textbook theory; it’s the kind of knowledge defense techs use for real electronic warfare. And since it’s out there in bite-sized chunks, we hackers can easily put it to good use.

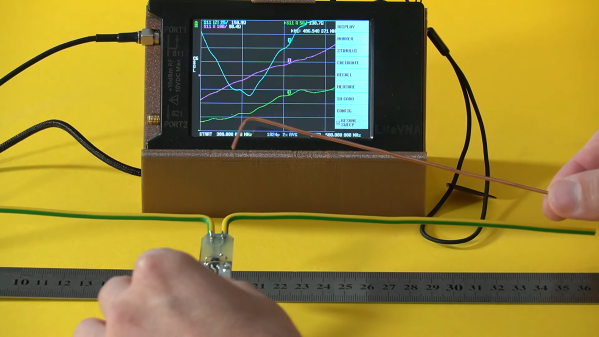

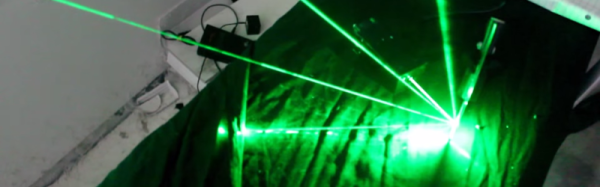

The key takeaway is that antenna size matters. Basically, it’s all about wavelength, and [Jonathan] hammers home how tuning antenna dimensions to your target frequency makes or breaks your signal. Whether you’re into omnis (for example, for 360-degree drone control) or laser-focused directional antennas for secret backyard links, this is juicy stuff.

If you’re serious about getting into RF hacking, watch this webinar. Then dig up that Yagi build, and be sure to send us your best antenna hacks.

Continue reading “A Hacker’s Approach To All Things Antenna”