To quote the greatest philosopher of the 20th century: “The future ain’t what it used to be.” Take personal assistants such as Amazon Echo and Google Home. When first predicted by sci-fi writers, the idea of instant access to the sum total of human knowledge with a few utterances seemed like a no-brainer; who wouldn’t want that? But now that such things are a reality, having something listening to you all the time and potentially reporting everything it hears back to some faceless corporate monolith is unnerving, to say the least.

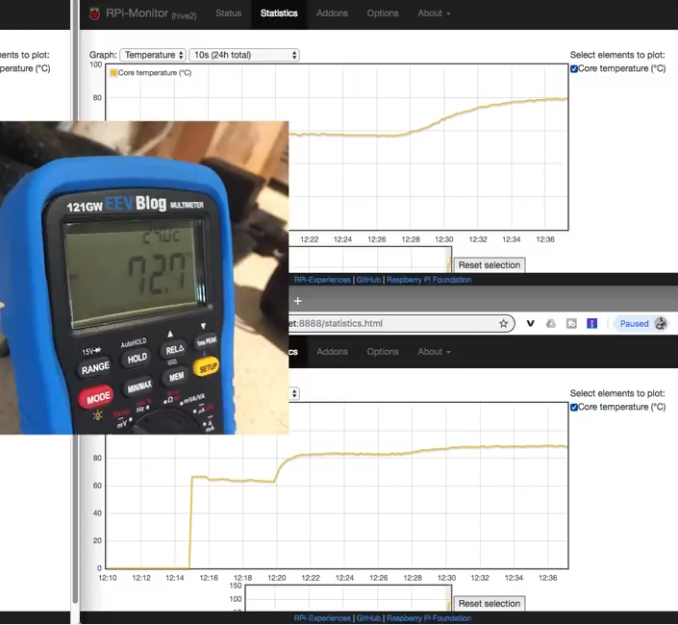

There’s a fix for that, though, with this cone of silence for your smart speaker. Dubbed “Project Alias” by [BjørnKarmann], the device consists of a Raspberry Pi with a couple of microphones and speakers inside a 3D-printed case. The Pi is programmed to emit white noise from its speakers directly into the microphones of the Echo or Home over which it sits, masking out the sounds in the room while simultaneously listening for a hot-word. It then mutes the white noise, plays a clip of either “Hey Google” or “Alexa” to wake the device up, and then business proceeds as usual. The bonus here is that the hot-word is customizable, so that in addition to winning back a measure of privacy, all the [Alexas] in your life can get their names back too. The video below shows people interacting with devices named [Doris], [Marvin], [Petey], and for some reason, [Milkshake].

We really like this idea, and the fact that no modifications are needed to the smart speaker is pretty slick, as is the fact that with a few simple changes to the code and the print files it can be used with any smart speaker. And some degree of privacy from the AI that we know is always listening through these things is no small comfort either.

Continue reading “Win Back Some Privacy With A Cone Of Silence For Your Smart Speaker”