Modern computers are incredible feats of engineering, but there are many that still yearn for the simpler times. When keyboards clacked and a desktop computer quite literally dominated the top of your desk. There’s a whole community of folks who scratch that itch by restoring vintage computers, but not everyone has the time, money, or skill for such pursuits. Plus, even the most lovingly cared for Apple II isn’t going to help you watch YouTube.

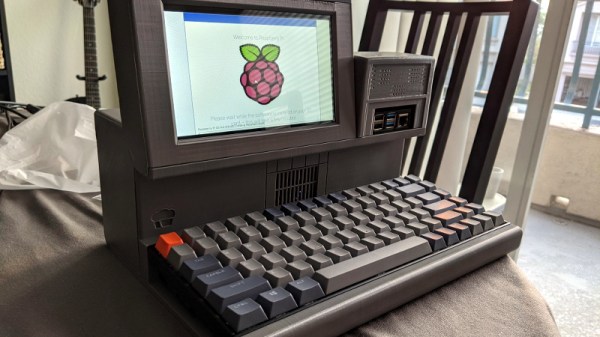

Those who wish to recreate the look and feel of a vintage computer with modern internals will certainly be interested in the HALWOP by [Maz_Baz]. While its 3D printed case isn’t a replica of any one computer, it does draw inspiration from iconic machines like the Apple Lisa and IBM XT. It’s an amalgamation of design ideas that seemed like a good idea circa 1982 or so, with plenty of 90° angles and air vents to go around.

Considering the size of the Raspberry Pi 4 that powers the HALWOP, most of the case is just hollow plastic. But of course, the whole idea depends on it being almost comically large. On the plus side, [Maz_Baz] says you can use one of those empty compartments to hold a Anker PowerCore 26800 battery pack. At least in theory that makes it a “luggable” computer, though good luck trying to move it around.

Considering the size of the Raspberry Pi 4 that powers the HALWOP, most of the case is just hollow plastic. But of course, the whole idea depends on it being almost comically large. On the plus side, [Maz_Baz] says you can use one of those empty compartments to hold a Anker PowerCore 26800 battery pack. At least in theory that makes it a “luggable” computer, though good luck trying to move it around.

In addition to the Pi 4 and battery pack, the HALWOP also uses a seven-inch touch LCD and Keychron K2 Bluetooth mechanical keyboard. Since everything is so modular, assembly is about as simple as it gets. Outside of the USB cables that power everything, you just need a long enough ribbon cable to connect the LCD to the Pi.

We know the purists don’t like the idea of a “retro” computer based on the Raspberry Pi, but of course, such projects aren’t about maintaining historical accuracy. They are a way to bridge the gap between modern technology and the unique aesthetics of a bygone era. Designs like the HALWOP allow a new generation to experience a taste of what computing was like in the early days, without giving up the ground that’s been gained in the intervening years.