We all know that it’s easy to get caught out by fake electronic components these days, with everything from microcontrollers to specialized ASICs being fair game. More recently, retro components that were considered obsolete decades ago are now becoming increasingly popular, with the unijunction transistor (UJT) a surprising example of this. The [En Clave de Retro] YouTube channel released a video (Spanish, with English dub) documenting fake UJTs bought off AliExpress.

These AliExpress UJTs were discovered after comments to an earlier video on real UJTs said that these obsolete transistors are still being manufactured and can be bought everywhere, meaning mostly on AliExpress and Amazon. Of course, this had to be investigated, as why would anyone still manufacture UJTs today, and did some Chinese semiconductor factory really spin up a new production line for them?

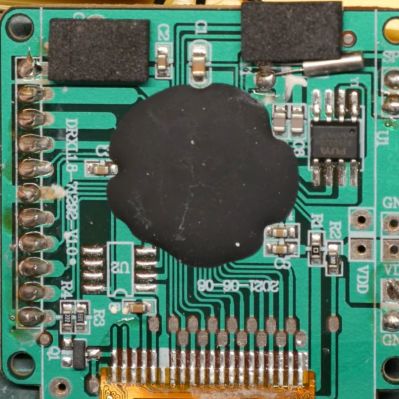

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some tests later and after a quick decapping of the metal can, the inside revealed a bipolar transistor (BJT) die (see top image on the left). Specifically, a PNP BJT transistor die, packaged up inside a vintage-style metal can with fake markings claiming it is a 2N2646 UJT.

The video suggests that scams like these might be because people want to get vintage parts for cheap, and that’s created a new market for people who would rather get scammed than deal with the sticker shock of paying for genuine new-old-stock or salvaged components. For example, while programmable unijunction transistors (PUTs) like the 2N6028 are still being manufactured, they cost a few dollars a pop in low quantities. UJTs used to be common in timer circuits, but now we have the 555.

Continue reading “The Scourge Of Fake Retro Unijunction Transistors”