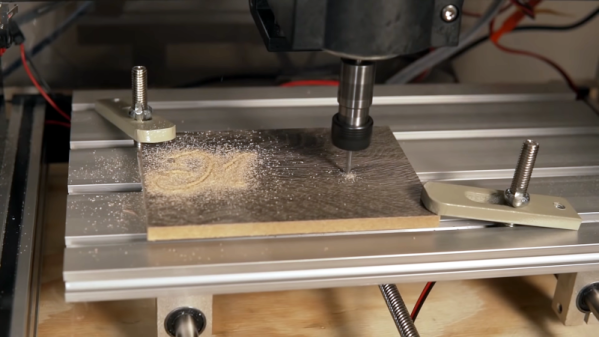

Low cost 3D printers have come a long way in the last few years, but have entry-level CNC machines improved by the same leaps and bounds? That’s what [ModBot] recently set out to find. Despite getting burned pretty badly on a cheap CNC a few years back, he decided to try again with a sub $400 machine from FoxAlien. You can see his full review after the break.

The machine looks very similar to other generic CNC machines you see under many brand names, sometimes for a good bit less. The 3018 number is a giveaway that the work area is 30×18 cm and a quick search pulled up several similar machines for just a bit more than $200. The FoxAlien did have a few nice features, though. It has a good-looking build guide and an acrylic box to keep down the shaving debris in your shop. There are also some other nice touches like a Z-axis probe and end stops. If you add those items to the cut-rate 3018 machines, the FoxAlien machine is pretty price competitive when you buy it from the vendor’s website. The Amazon page in the video shows $350 which is a bit more expensive but does include shipping.

As with most of these cheap CNC machines, one could argue that it’s more of an engraver than a full mill. But on the plus side, you can mount other tools and spindles to get different results. You can even turn one of these into a diode laser cutter, but you might be better off with something purpose-built unless you think you’ll want to switch back and forth often.

This reminded us of a CNC we’ve used a lot, the LinkSprite. It does fine for about the same price but we are jealous of the enclosure. Of course, half the fun of owning something like this is hacking it and there are plenty of upgrades for these cheap machines.

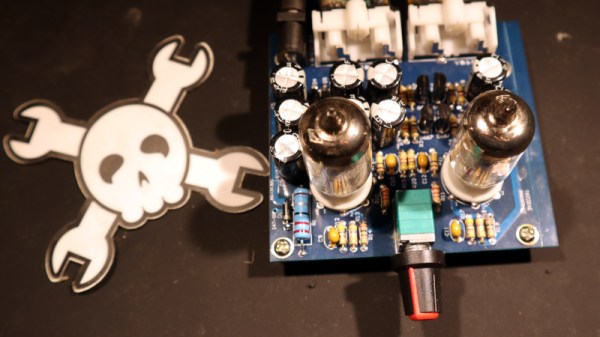

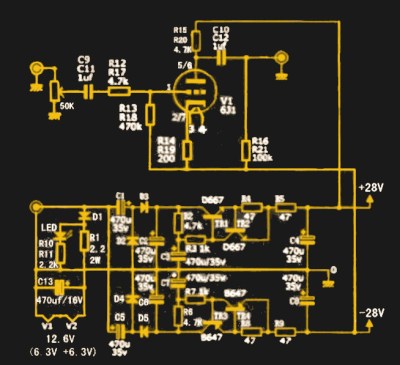

What I received for my tenner was a press-seal bag with a PCB and a pile of components, and not much else. No instructions, which would have been worrisome were the board not clearly marked with the value of each component. The circuit was on the vendor’s website and is so commonly used for these sort of kits that it can be found all over the web — a very conventional twin common-cathode amplifier using a pair of 6J1 miniature pentodes, and powered through a +25 V and -25 V supply derived from a 12 VAC input via a voltage multiplier and regulator circuit. It has a volume potentiometer, two sets of phono sockets for input and output, and the slightly naff addition of a blue LED beneath each tube socket to impart a blue glow. I think I’ll pass on that component.

What I received for my tenner was a press-seal bag with a PCB and a pile of components, and not much else. No instructions, which would have been worrisome were the board not clearly marked with the value of each component. The circuit was on the vendor’s website and is so commonly used for these sort of kits that it can be found all over the web — a very conventional twin common-cathode amplifier using a pair of 6J1 miniature pentodes, and powered through a +25 V and -25 V supply derived from a 12 VAC input via a voltage multiplier and regulator circuit. It has a volume potentiometer, two sets of phono sockets for input and output, and the slightly naff addition of a blue LED beneath each tube socket to impart a blue glow. I think I’ll pass on that component.