Intel announced CrossTalk, a new side-channel attack that can leak data from CPU buffers. It’s the same story we’ve heard before. Bits of internal CPU state can be inferred by other processes. This attack is a bit different, in that it can leak data across CPU cores. Only a few CPU instructions are vulnerable, like RDRAND, RDSEEED, and EGETKEY. Those particular instructions matter, because they’re used in Intel’s Secure Enclave and OpenSSL, to name a couple of important examples.

Continue reading “This Week In Security: Crosstalk, TLS Resumption, And Brave Shenanigans”

Security Hacks1541 Articles

Quantum Computing And The End Of Encryption

Quantum computers stand a good chance of changing the face computing, and that goes double for encryption. For encryption methods that rely on the fact that brute-forcing the key takes too long with classical computers, quantum computing seems like its logical nemesis.

For instance, the mathematical problem that lies at the heart of RSA and other public-key encryption schemes is factoring a product of two prime numbers. Searching for the right pair using classical methods takes approximately forever, but Shor’s algorithm can be used on a suitable quantum computer to do the required factorization of integers in almost no time.

When quantum computers become capable enough, the threat to a lot of our encrypted communication is a real one. If one can no longer rely on simply making the brute-forcing of a decryption computationally heavy, all of today’s public-key encryption algorithms are essentially useless. This is the doomsday scenario, but how close are we to this actually happening, and what can be done?

Continue reading “Quantum Computing And The End Of Encryption”

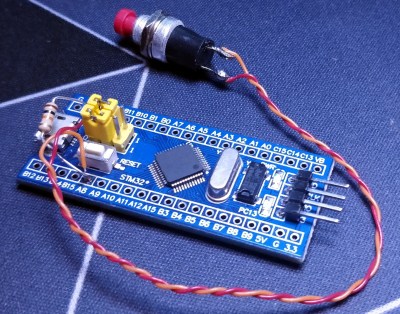

STM32 Blue Pill Turned GPG Security Token

Feeling the cost of commercial options like the YubiKey and Nitrokey were too high, [TheStaticTurtle] started researching DIY alternatives. He found an open source project allows the STM32F103 to act as a USB cryptographic token for GNU Privacy Guard, which was a start. All he had to do was build a suitable device to install it on.

The first step was to test the software out on the popular “Blue Pill” development board, which [TheStaticTurtle] documents in the write-up should anyone want to give it a try themselves. The ST-Link V2 was already a supported target, so it only took some relatively minor tweaks to get running and add support for a simple push button. The output of gpg --card-status showed the device was working as expected, so with the software sorted, it was time to take a closer look at the hardware.

To create his “TurtleAuth” dongle, [TheStaticTurtle] started with the basic layout of the Blue Pill and added in a TTP223E touch control IC. The original Micro USB port was also swapped for a male USB-A connector so the device could be plugged directly into a computer. An upper PCB, containing the status LEDs and touch pad, was then designed so it would fit over the main board as an enclosure of sorts. While the sides are still open, the device looks robust enough to handle life in a laptop bag at least.

While it’s not exactly a common project, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen somebody spin up their own hardware token. More evidence of what the dedicated individual can accomplish these days on a relatively limited budget.

This Week In Security: Exim, Apple Sign-in, Cursed Wallpaper, And Nuclear Secrets

So first off, remember the Unc0ver vulnerability/jailbreak from last week? In the 13.5.1 iOS release, the underlying flaw was fixed, closing the jailbreak. If you intend to jailbreak your iOS device, make sure not to install this update. That said, the normal warning applies: Be very careful about running out-of-date software.

Apple Sign In

An exploit in Apple’s web authentication protocol was fixed in the past week . Sign In With Apple is similar to OAuth, and allows using an Apple account to sign in to other sites and services. Under the hood, a JSON Web Token (JWT) gets generated and passed around, in order to confirm the user’s identity. In theory, this scheme even allows authentication without disclosing the user’s email address.

So what could go wrong? Apparently a simple request for a JWT that’s signed with Apple’s public key will automatically be approved. Yeah, it was that bad. Any account linked to an Apple ID could be trivially compromised. It was fixed this past week, after being found and reported by [Bhavuk Jain]. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Exim, Apple Sign-in, Cursed Wallpaper, And Nuclear Secrets”

This Week In Security: Leaking Partial Bits, Apple News, And Overzealous Contact Tracing

Researchers at the NCCGroup have been working on a 5-part explanation of a Windows kernel vulnerability, targeting the Kernel Transaction Manager (KTM). The vulnerability, CVE-2018-8611, is a local privilege escalation bug. There doesn’t seem to be a way to exploit this remotely, but it is an interesting bug, and NCCGroup’s work on it is outstanding.

They start with a bit of background on what the KTM is, and why one might want to use it. Next is a handy guide to reverse engineering Microsoft patches. From there, they describe the race condition and how to actually exploit it. They cover a wide swath in the series, so go check it out.

Left4Dead 2

Just a reminder that bugs show up where you least expect them, [Hunter Stanton] shares his story of finding a code execution bug in the popular Valve game, Left4Dead 2. Since the game’s code isn’t available to look at, he decided to go the route of fuzzing. The specific approach he took was to fuzz the navigation mesh data, part of the data contained in each game map. Letting the Basic Fuzzing Framework (BFF) run for three days turned up a few possible crashes, and the most promising turned out to have code execution potential. [Hunter] submitted the find through Valve’s HackerOne bug bounty program, and landed a cool $10k bounty for his trouble.

While it isn’t directly an RCE, [Hunter] does point out that malicious mesh data could be distributed with downloadable maps on the Steam workshop. Alternatively, it should be possible to set up a fake game server that distributes the trapped map. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Leaking Partial Bits, Apple News, And Overzealous Contact Tracing”

Home Assistant Get Fingerprint Scanning

Biometrics — like using your fingerprint as a password — is certainly convenient and are pretty commonplace on phones and laptops these days. While their overall security could be a problem, they certainly fit the bill to keep casual intruders out of your system. [Lewis Barclay] had some sensors gathering dust and decided to interface them to his Home Assistant setup using an ESP chip and MQTT.

You can see the device working in the video below. The code is on GitHub, and the only thing we worried about was the overall security. Of course, the security of fingerprint scanners is debatable since you hear stories about people lifting fingerprints with tape and glue, but even beyond that, if you were on the network, it would seem like you could sniff and fake fingerprint messages via MQTT. Depending on your security goals, that might not be a big deal and, of course, that assumes someone could compromise your network to start with.

Hiding Malware, With Windows XP

In the nearly four decades since the first PC viruses spread in the wild, malware writers have evolved some exceptionally clever ways to hide their creations from system administrators and from anti-virus writers. The researchers at Sophos have found one that conceals itself as probably the ultimate Trojan horse: it hides its tiny payload in a Windows XP installation.

The crusty Windows version is packaged up with a copy of an older version of the VirtualBox hypervisor on which to run it. A WIndows exploit allows Microsoft Installer to download the whole thing as a 122 MB installer package that hides the hypervisor and a 282 MB disk image containing Windows XP. The Ragnar Locker ransomware payload is a tiny 49 kB component of the XP image, which the infected host will run on the hypervisor unchallenged.

The Sophos analysis has a fascinating delve into some of the Windows batch file tricks it uses to probe its environment and set up the connections between host and XP, leaving us amazed at the unorthodox use of a complete Microsoft OS and that seemingly we have reached a point of system bloat at which such a large unauthorised download and the running of a complete Microsoft operating system albeit one from twenty years ago in a hypervisor can go unnoticed. Still, unlike some malware stories we’ve seen, at least this one is real.