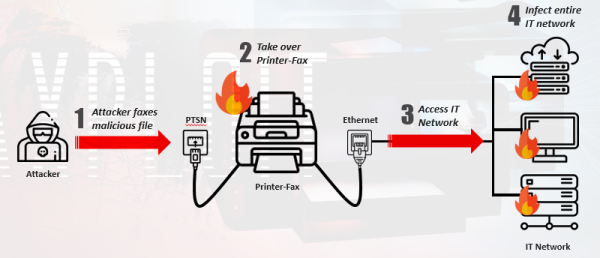

Whatsapp allows for end-to-end encrypted messaging, secure VoIP calls, and until this week, malware installation when receiving a call. A maliciously crafted SRTCP connection can trigger a buffer overflow, and execute code on the target device. The vulnerability was apparently found first by a surveillance company, The NSO Group. NSO is known for Pegasus, a commercial spyware program that they’ve marketed to governments and intelligence agencies, and which has been implicated in a number of human rights violations and even the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi. It seems that this Whatsapp vulnerability was one of the infection vectors used by the Pegasus program. After independently discovering the flaw, Facebook pushed a fixed client on Monday.

Windows XP Patched Against Wormable Vulnerability

What year is it!? This Tuesday, Microsoft released a patch for Windows XP, five years after support for the venerable OS officially ended. Reminiscent of the last time Microsoft patched Windows XP, when Wannacry was the crisis. This week, Microsoft patched a Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) vulnerability, CVE-2019-0708. The vulnerability allows an attacker to connect to the RDP service, send a malicious request, and have control over the system. Since no authentication is required, the vulnerability is considered “wormable”, or exploitable by a self-replicating program.

Windows XP through Windows 7 has the flaw, and fixes were rolled out, though notably not for Windows Vista. It’s been reported that it’s possible to download the patch for Server 2008 and manually apply it to Windows Vista. That said, it’s high time to retire the unsupported systems, or at least disconnect them from the network.

The Worst Vulnerability Name of All Time

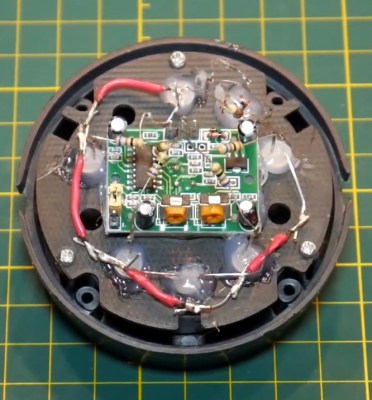

Thrangrycat. Or more accurately, “😾😾😾” is a newly announced vulnerability in Cisco products, discovered by Red Balloon Security. Cisco uses secure boot on many of their devices in order to prevent malicious tampering with device firmware. Secure boot is achieved through the use of a secondary processor, a Trust Anchor module (TAm). This module ensures that the rest of the system is running properly signed firmware. The only problem with this scheme is that the dedicated TAm also has firmware, and that firmware can be attacked. The TAm processor is actually an FPGA, and researchers discovered that it was possible to modify the FPGA bitstream, totally defeating the secure boot mechanism.

The name of the attack, thrangrycat, might be a satirical shot at other ridiculous vulnerability names. Naming issues aside, it’s an impressive bit of work, numbered CVE-2019-1649. At the same time, Red Balloon Security disclosed another vulnerability that allowed command injection by an authenticated user.

Odds and Ends

See a security story you think we should cover? Drop us a note in the tip jar!