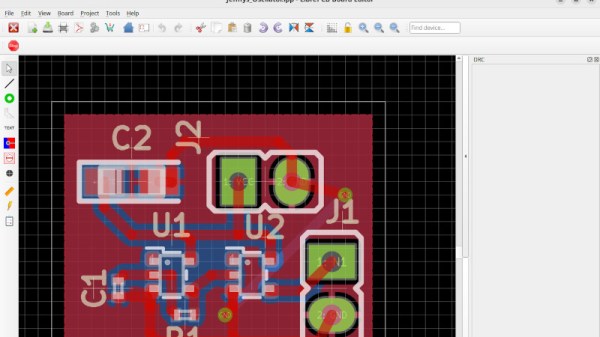

Nearly three years ago at the start of 2020 and before the pandemic hit, we took a look at an up-and-coming player in the world of PCB design. LibrePCB is by no means as old as the more established players, but at the time it was joining the ranks of open-source EDA packages with its first early stable releases. It showed a lot of promise but was still a little rough around the edges back then, but in the years since it’s advanced to the extent that in September they released version 1.0. That’s a significant moment for any open source package, so it’s time to return and take another look. It’s a cross-platform package with builds available for Linux, Windows, MacOS and FreeBSD, of which I needed the Linux version. There are one or two options to choose from, I went for the appImage as probably the least trouble. Very quickly I was in a new EDA package, and I set out to make a simple Schmitt trigger oscillator as a test project. Continue reading “Review: LibrePCB Hits Version 1.0”

Software Hacks1037 Articles

The End Of Basic?

Many people, one way or another, got started programming computers using some kind of Basic. The language was developed at Dartmouth specifically so people could write simple programs without much training. However, Basic found roots in small computers and grew to where it is today, virtually unrecognizable. Writing things in something like Visual Basic may be easier than some programming tasks, but it requires a lot of tools and some reading or training. We aren’t sure where the name EndBasic came from, but this program — written in Rust — aims to bring Basic back to a simpler time. Sort of.

You can run the program in a browser, locally, or connected to a cloud service. It looks like old-fashioned Basic at first. But the more you dig in, the odder it gets. The command line is more akin to a Python REPL. You type things, and they happen. It took a while to figure out that you need to enter EDIT to write a program. Then, what you type gets saved until you press escape. The syntax is Basic-like but has oddities. There are no line numbers, but you can use labels that start with an at sign.

Chromebooks Now Get Ten Years Of Software Updates

It’s an acknowledged problem with the mobile phone industry and particularly within the Android ecosystem, that the operating system support on a typical device can persist for far too short a time, leaving the user without critical security updates. With the rise of the Chromebook, this has moved into larger devices, with schools and other institutions left with piles of what’s essentially e-waste.

Now in a rare show of sense from a tech company, Google have announced that Chromebooks are to receive ten years of updates from next year. Even better, it seems that this will be retroactively applied to at least some older machines, allowing owners to opt in to further updates for the remainder of the decade following the machine’s launch.

Of course, a Chrome OS upgrade on an older machine won’t make it any quicker. We’re guessing many users will feel the itch up upgrade their hardware long before their decade of software support is up. But anything which saves e-waste has to be applauded, and since this particular scribe has a five-year-old ASUS Transformer just out of support, we’re hoping for a chance to jump back on that train.

There’s another question though, and it relates to the business model behind Chromebooks. We doubt that the hardware manufacturers are thrilled at their customers’ old machines receiving a new lease of life and we doubt Google are doing this through sheer altruism, so we’re guessing that the financial justification comes from an extra five years of making money from the users’ data.

PyOBD Gets Python3 Upgrades

One of the best things about open source software is that, instead of being lost to the ravages of time like older proprietary software, anyone can dust off an old open source program and bring it up to the modern era. PyOBD, a python tool for interfacing with the OBD system in modern vehicles, was in just such a state with its latest version still being written in Python 2 which hasn’t had support in over three years. [barracuda-fsh] rewrote the entire program for Python 3 and included a few other upgrades to it as well.

Key feature updates with this version besides being completely rewritten in Python 3 include enhanced support for OBD-II commands as well as automating the detection of the vehicle’s computer capabilities. This makes the program much more plug-and-play than it would have been in the past. PyOBD now also includes the python-OBD library for handling the actual communication with the vehicle, while PyOBD provides the GUI for configuring and visualizing the data given to it from the vehicle. An ELM327 adapter is required.

With options for Mac, Windows, or Linux, most users will be able to make use of this software package provided they have the necessary ELM327 adapter to connect to their vehicle. OBD is a great tool as passenger vehicles become increasingly computer-driven as well, but there are some concerns surrounding privacy and security in some of the latest and proposed versions of the standard.

BingGPT Brings AI Chat To The Desktop

Interested in AI, but sick of using everything in a browser? Miss clicking on a good old desktop icon to open a local bit of software? In that case, BingGPT could be just the thing for you.

It’s nothing too crazy—just a desktop application that gives you access to Bing’s AI-powered chatbot. It’s available on a range of platforms, from Windows, to Apple, and Linux, and binaries are available for Intel, Apple Silicon, and ARM processors.

Using BingGPT is simple. Sign in with your Microsoft account, and away you go. There’s no need to use Microsoft Edge or any ugly browser plugins, and you can export your conversations to Markdown, PNG, and PDF for sharing beyond the program. It’s also complete with a range of keyboard shortcuts to speed your interaction with the large language model when it gets off track. There’s also the Compose button which can actually go ahead and write stuff for you.

Fundamentally, all the cool stuff is still coming in via the web, but it’s nice to be able to use Bing’s chatbot without having to succumb to the horrors of a Microsoft browser. It’s interesting to see how large language models are becoming an all-pervasive tool of late. If you’re building your own nifty projects in this area, don’t hesitate to let us know!

Balloon-Eye View Via Ham Radio

If you’ve ever thought about launching a high-altitude balloon, there’s much to consider. One of the things is how do you stream video down so that you — and others — can enjoy the fruits of your labor? You’ll find advice on that and more in a recent post from [scd31]. You’ll at least enjoy the real-time video recorded from the launch that you can see below.

The video is encoded with a Raspberry Pi 4 using H264. The MPEG-TS stream feeds down using 70 cm ham radio gear. If you are interested in this sort of thing, software, including flight and ground code, is on the Internet. There is software for the Pi, an STM32, plus the packages you’ll need for the ground side.

We love high-altitude balloons here at Hackaday. San Francisco High Altitude Ballooning (SF-HAB) launched a pair during last year’s Supercon, which attendees were able to track online. We don’t suggest you try to put a crew onboard, but there’s a long and dangerous history of people who did.

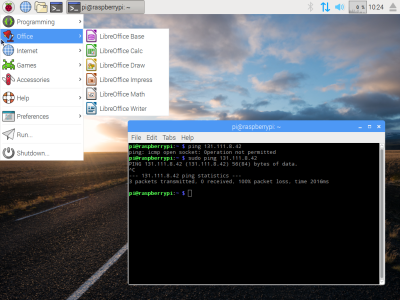

Jenny’s Daily Drivers: Raspberry Pi Desktop

One of the more exciting prospects upon receiving one of the earliest Raspberry Pi boards back in 2012 was that it was a fully-functional desktop computer in the palm of your hand. In those far-off days, the Debian OS distro for the board wasn’t even yet called Raspbian, but it would run a full-on desktop on your TV and you could use it after a fashion to browse the web or do wordprocessing. It wasn’t in any way fast, but it was usable enough to be more than a novelty. I’ve said before on these pages that the Raspberry Pi folks’ key product is their OS rather than their computers. While they rarely have the fastest or highest spec hardware, you can depend on Raspberry Pi OS being updated and supported through the life of the board unlike many of their competitors. I can download their latest OS image and still run it on that 2012 board, which to me ranks as a very laudable achievement.

The OS They Don’t Really Tell You About

Raspberry Pi OS doesn’t run on any other ARM single board computers but their own, but it’s not quite accurate to say that it only runs on Raspberry Pi hardware. Since 2016 when it was launched as PIXEL, the folks in Cambridge have also maintained a PC version for 32-bit i386 computers, now called Raspberry Pi Desktop. It may be the Pi product they don’t talk about much, but you can still find it on their downloads page.

Like the ARM version, it’s based on Debian and presents as close as possible to the environment you’d find on your Pi. I’m interested to see whether it still lives up to the claim of being usable on older hardware, so I’ve downloaded a copy and installed it on my trusty 2007 Dell Inspiron 640. It rocks a 1.6 GHz Core Duo with 4 GB of memory and a SATA SSD so it’s not the lowest spec hardware on the block, but by 2023’s standard it represents a giveaway-spec old laptop. Can I use it as a daily driver? Let’s find out! Continue reading “Jenny’s Daily Drivers: Raspberry Pi Desktop”