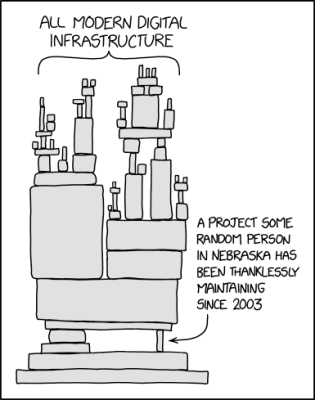

To the surprise of almost nobody, the unprecedented build-out of datacenters and the equipping of them with servers for so-called ‘AI’ has led to a massive shortage of certain components. With random access memory (RAM) being so far the most heavily affected and with storage in the form of HDDs and SSDs not far behind, this has led many to ask the question of how we will survive the coming months, years, decades, or however-long the current AI bubble will last.

One thing is already certain, and that is that we will have to make our current computer systems last longer, and forego simply tossing in more sticks of RAM in favor of doing more with less. This is easy to imagine for those of us who remember running a full-blown Windows desktop system on a sub-GHz x86 system with less than a GB of RAM, but might require some adjustment for everyone else.

In short, what can us software developers do differently to make a hundred MB of RAM stretch further, and make a GB of storage space look positively spacious again?

Continue reading “Surviving The RAM Apocalypse With Software Optimizations”