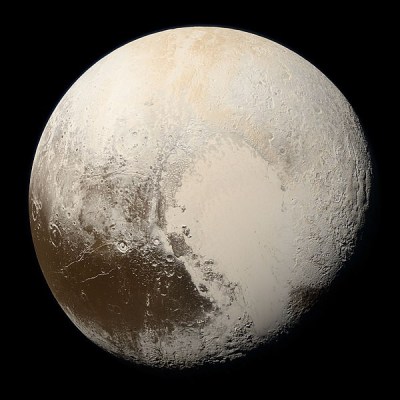

In 2015 NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft provided humanity with the first up-close views of Pluto, passing just 12,472 km (7,750 mi) from the surface. What had always been little more than a fuzzy blip at the edge of the solar system could finally be seen in stunning high resolution. Unfortunately, the deep space probe could only provide us with a relatively fleeting glimpse at the mysterious dwarf planet — the physics of such a distant interplanetary flight meant the energy required to slow down and enter orbit around Pluto was beyond the tiny spacecraft’s abilities.

The craft, often described as being roughly the size and shape of a grand piano, raced past Pluto and its moons at a relative velocity of approximately 49,600 km/h (30,800 mph) and headed out in the direction of Sagittarius. The incredible rate at which New Horizons traveled officially put it on track to be just the fifth spacecraft to leave the solar system, after the Pioneer and Voyager probes. Even so, its onboard systems were still in good health, and if given a sufficiently distant target, the $700 million craft was ready and able to collect more data.

Accordingly, almost exactly a year after it flew over Pluto, New Horizons officially received a mission extension from NASA. As it blasted through deep space, the craft would seek out and study as many objects as it could in the region of space known as the Kuiper belt. Given that there are no current plans to send other spacecraft through this distant area of the outer solar system, New Horizons was uniquely positioned to make what could be once-in-a-lifetime observations.

Or at least, that was the plan. Recently, notes from a May 4th meeting of the Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) were released that revealed NASA’s plans to redirect New Horizons from its work in the Kuiper belt to focus on heliospheric science in 2025. Those in attendance said the meeting became “heated” as New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern questioned the logic of potentially changing the craft’s mission this late in the game.

Continue reading “Change Of Plans For New Horizons Sparks Debate”