I don’t know why fidget spinners are only getting popular now. They’ve been selling like hotcakes on Tindie for a year now, and I’ve been seeing 3D printed versions around the Internet for almost as long. Nevertheless, fidget spinners — otherwise known as a device to turn a skateboard bearing into a toy — have become unbelievably popular in the last month or so. Whatever; I’m sure someone thinks my complete collection of Apollo 13 Pogs from Carl’s Jr. with modular Saturn V Pog carry case and aluminum slammer embossed with the real Apollo 13 mission patch is stupid as well.

However, a new fad is a great reason to drag out an oscilloscope, measure the rotation of a fidget spinner, take a video of the whole endeavor, and monetize it on YouTube. That’s just what [Frank Buss] did. It’s like he’s printing money at this point.

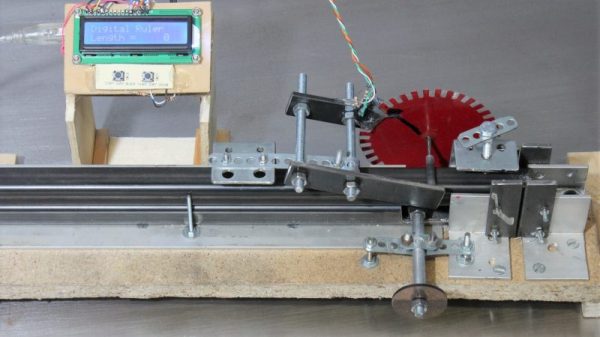

The measurement setup for this test is simple enough. [Frank] connected a small solar cell to the leads of his $2k oscilloscope, and placed the cell down on his workbench. This generated a voltage of about 28mV. Spinning the fidget spinner cast a shadow over the cell that was measured as a change in voltage. Oscilloscopes measure frequency, and by dividing that frequency by three, [Frank] calculated his fidget spinner was spinning at the remarkable rate of 2200 RPM.

Is this a stupid use of expensive equipment? Surprisingly no. The forty thousand videos on YouTube demonstrating a “99999+ RPM Fidget Spinner” all use cheap digital laser tachometers available for $20 on eBay. These tachometers top out at — you guessed it — 99999 RPM. Using only an oscilloscope and a solar cell [Frank] found in his parts drawer, he found an even better way to push the envelope of fidget spinner test and measurement.

Using this method, even an inexpensive 40MHz scope can reliably measure three-bladed fidget spinners up to 800,000,000 RPM. Of course, this calculation doesn’t take into account capacitance in the cell, you’ll need a margin for Nyquist, and everything within 20 meters will be destroyed, but there you go. A better way to measure the rotation speed of fidget spinners. It’s technically a hack.

You can check out [Frank]’s video of this experiment below. If you liked this post, don’t forget to like, rate, comment and subscribe for even more of the best Fidget Spinner news.

Continue reading “You Won’t Believe That Fidget Spinners Are Obvious Clickbait!”