[Don Eduardo] took matters into his own hands after experiencing a days-long power outage at his house. And like most of us have done at least one, he managed to burn his fingers on a regulator in the process. That’s because he prototyped a way to use power tool batteries as an emergency source — basing his circuit on a 7812 linear regulator which got piping hot in no time flat.

His next autodidactic undertaking carried him into the realm of switch-mode buck converters (learn a bit about these if unfamiliar). The device steps down the ~18V output to 12V regulated for devices meant for automotive or marine. We really like see the different solutions he came up with for interfacing with the batteries which have a U-shaped prong with contacts on opposite sides.

The final iteration, which is pictured above, builds a house of cards on top of the buck converter. After regulating down to 12V he feeds the output into a “cigarette-lighter” style inverter to boost back to 110V AC. The hardware is housed inside of a scrapped charger for the batteries, with the appropriate 3-prong socket hanging out the back. We think it’s a nice touch to include LED feedback for the battery level.

We would like to hear your thoughts on this technique. Is there a better way that’s as easy and adaptive (you don’t have to alter the devices you’re powering) as this one?

Continue reading “Emergency Power Based On Cordless Drill Batteries”

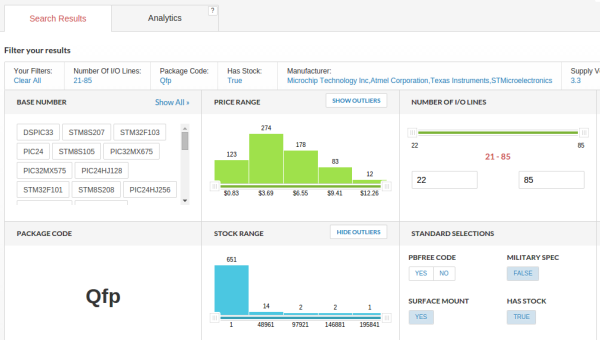

A couple of years ago he worked on a standalone chemical sensor and had a few extra boards sitting around after the project was done. As any resourceful hacker will do, he reached for them as the closest and easiest solution when needing to log data as a quick test. It wasn’t for quite some time that he went back to try out commercially available loggers and found a problem in doing so.

A couple of years ago he worked on a standalone chemical sensor and had a few extra boards sitting around after the project was done. As any resourceful hacker will do, he reached for them as the closest and easiest solution when needing to log data as a quick test. It wasn’t for quite some time that he went back to try out commercially available loggers and found a problem in doing so.