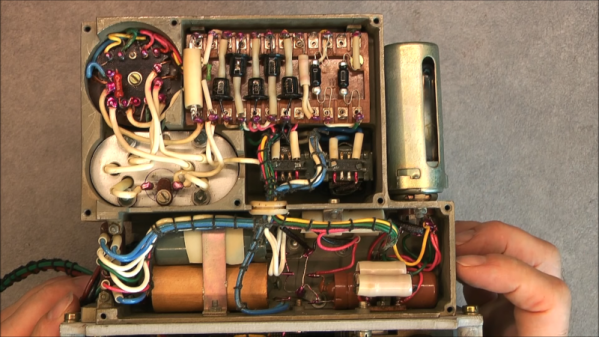

NFC hacking can be a daunting task with many specialized tools, a proliferation of protocols, and a multitude of different devices. [ElectronicCats] has done a lot of work to try to make this investigation accessible by creating an open-source, hardware-certified NFC tool called the HunterCatNFC that can read and emulate a multitude of NFC devices.

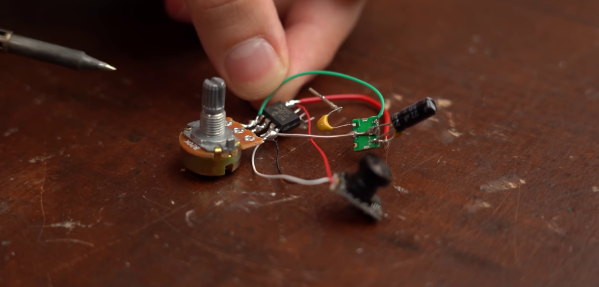

The HunterCatNFC device is meant to be portable and self contained, with LED indicator lights that can give information about the various modes, and feedback about what data is being received. At its core, the HunterCatNFC has an NXP PN7150 NFC controller chip to handle the NFC communication. The main processing controller is a Microchip SAMD21 which also provides USB functionality, and the whole device is powered by a 3.7V 150mAh Li-ion battery.

The HunterCatNFC has three main modes, ’emulation’, ‘read/write’ and ‘peer-to-peer’. Emulation mode allows the HunterCatNFC to mimic the functionality of a passive NFC device, only responding when an NFC reader issues a request. The read/write mode allows it to emulate an NFC reader or writer, with the ability to communicate with nearby passive NFC devices. The peer-to-peer mode gives the device the ability to have two way communication, for instance, between two HunterCatNFC devices.

We’ve covered NFC hacking before, including the Flipper Zero. The HunterCatNFC is a fine addition to the NFC hackers arsenal of tools with some very nice documentation to learn from. For those not wanting to send out their own boards to be printed and assembled, [ElectronicCats] has them for sale.

Video after the break!

Continue reading “Hunt Down NFC Signals With This NFC Multi Tool”