You’re on a home router, and your IP address keeps changing. Instead of paying a little bit extra for a static IP address (and becoming a grownup member of the Internet) there are many services that let you push your current IP out to the rest of the world dynamically. But most of them involve paying money or spending time reading advertisements. Who has either money or time?!

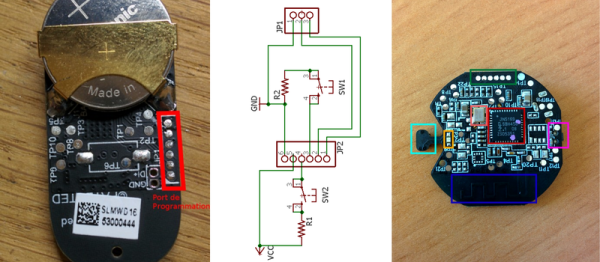

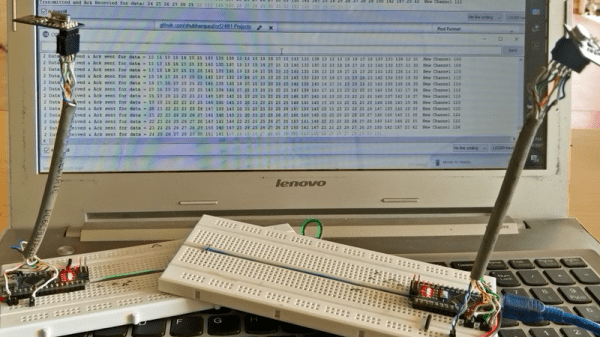

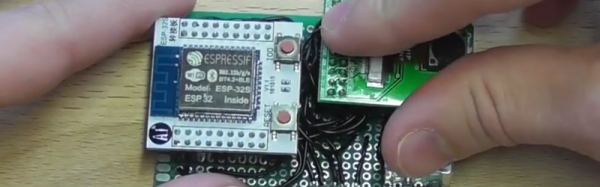

[Alberto Ricci Bitti] cobbled together a few free services and an ESP8266 module to make a device that occasionally pushes its external IP address out to a web-based “dweet” service. The skinny: an ESP8266 gets its external IP address from ipify.org and pushes it by “dweet” to a web-based data store. Freeboard reads the “dweet” and posts the resulting link in a nice format.

Every part of this short chain of software services could be replaced easily enough with anything else. We cobbled together our own similar solution, literally in the previous century, back when we were on dialup. But [Alberto R B]’s solution is quick and easy, and uses no fewer than three (3!) cloud services ending in .io. Add an ESP8266 to the WiFi network that you’d like to expose, and you’re done.

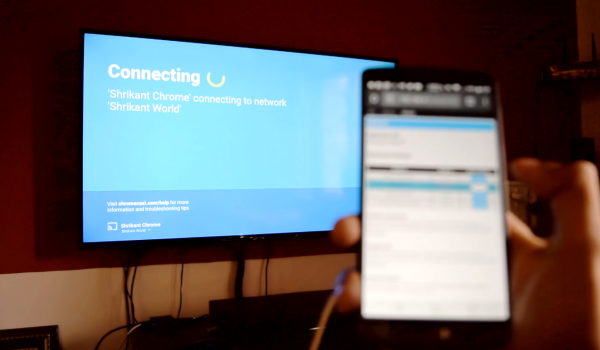

The jammer is an ESP8266 development board — running some additional custom code — accessed and controlled by a cell phone. From the interface, [Nimbalkar] is able to target a WiFi network and boot all the devices off the network by de-authenticating them. Another method is to flood the airspace with bogus SSIDs to make connecting to a valid network a drawn-out affair.

The jammer is an ESP8266 development board — running some additional custom code — accessed and controlled by a cell phone. From the interface, [Nimbalkar] is able to target a WiFi network and boot all the devices off the network by de-authenticating them. Another method is to flood the airspace with bogus SSIDs to make connecting to a valid network a drawn-out affair.