It’s a truism that a computer must boot before it begins to operate. Nowadays that bootstrapping process is automatic, but in the case of the very first home computers, it was very much a hands-on affair. That’s what all those switches and blinkenlights are for on the front panel of the Altair 8800 — laboriously flicking each bit into memory as required to get your program going.

[Linus Åkesson] missed those very early days, and wanted to see what it was like, and clicking virtual switches on an emulator wasn’t going to cut it. He realized that he could set up an ATmega88 for front-panel booting, and proceeded to do just that.

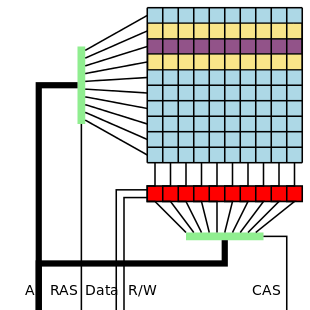

The article linked above goes into good detail; for those of you who prefer video, we’ve embedded his presentation below. They say the book is always better, but to get the full story, you’ll really want both in this case. The video contains a lot more context and build details, but neglects to mention some issues he had with programming that are detailed in the text. In short, the Write Page bit needs to be written to the Command register to use the page buffer. Which does make sense, but tripped [Linus] up at first.

Then again, this use case isn’t exactly detailed in the datasheet. ATmega88 is an old chip, but not Intel 8008 old, so that’s no surprise. Which is exactly what makes this a good hack! The only thing lacking is blinkenlights to allow one to see the contents of the registers. [Linus] discusses the idea of putting them in, but is apparently happy with this more minimalist approach.

We’ve seen the doughty Atmel chip hacked into everything from web-servers to washing machines, and even things that don’t start with “W”. As for the redoubtable [Linus], he’s most famous around these parts for his musical inventions and adventures with the Commodore 64. Continue reading “Give ATMega88 The Boot With This Retro Front Panel”