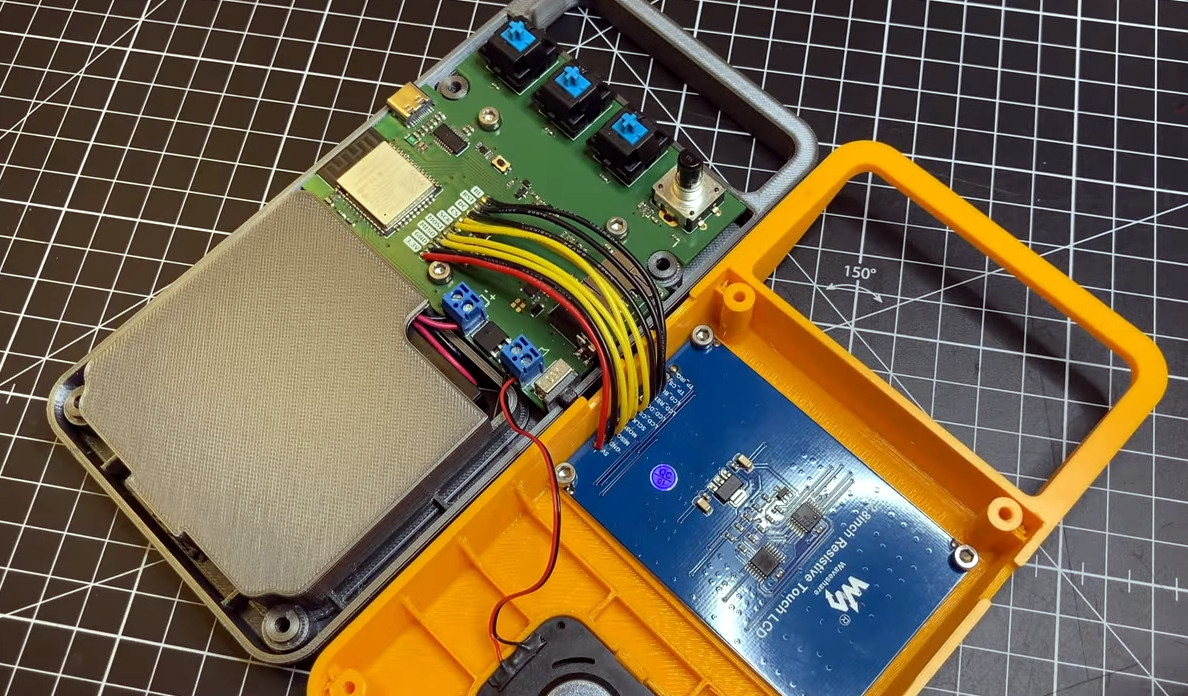

At first glance, this gorgeous retro-styled audio player built by [Max Kern] could absolutely pass for the genuine article. But then you take a closer look and realize that the “tape” it’s playing is actually an animation running on a 320 x 240 IPS display, and the Play and Rewind buttons on the front aren’t the chunky electromechanical affairs of yesteryear but actually cleverly repurposed MX keyboard switches.

By now you’re probably realizing that this player is quite a bit smaller than you first imagined, which in turn, means that it even its case is a modern fabrication. While it might perfectly encapsulate the look and feel of a piece of 1980s consumer electronics, it was squirted out on a thoroughly modern desktop 3D printer.

By now you’re probably realizing that this player is quite a bit smaller than you first imagined, which in turn, means that it even its case is a modern fabrication. While it might perfectly encapsulate the look and feel of a piece of 1980s consumer electronics, it was squirted out on a thoroughly modern desktop 3D printer.

Even so, [Max] made sure to include draft angles in the CAD design and and a distinctive separation line so the case looked like it was injection molded. Following similar logic, he decided against using a modern rechargeable battery pack to power the electronics, opting instead for a more era-appropriate set of AA batteries.

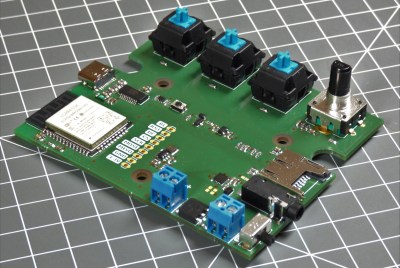

In terms of hardware, the custom PCB is home to an ESP32 WROOM, a MAX98357A I2S audio amplifier, a FT231XS USB-to-serial chip, with enough passives and regulators to keep them all well fed and happy. The ESP32 has more than enough computational horsepower to chew through MP3 files, which are conveniently loaded via an SD slot built into the side of the player. As the player was actually intended for audio books, onboard playback is limited to a mono speaker; though there is a 3.5 mm audio jack to plug in a pair of headphones for when the built-in speaker isn’t up to the task.

Check out the video after the break to see how the player is assembled, as well as a demonstration of its simple three-button user interface. It looks like a joy to use, though the lack of fast forward and rewind sound effects took us a bit by surprise given the otherwise impeccable attention to detail. We’ll assume there’s some technical limitation that makes this particularly difficult to implement, and that their absence is currently keeping [Max] up at night.

As impressive as the final product is, we can’t say it’s a surprise. Frankly, we wouldn’t expect anything less from [Max] at this point. His adaptive OLED macro pad wowed us back in 2020, and his ZeroBot is still one of the slickest designs for a DIY two-wheeled robots we’ve ever seen.

Continue reading “Faux-Retro “Tape” Player Runs On ESP32 And 80s Vibes”