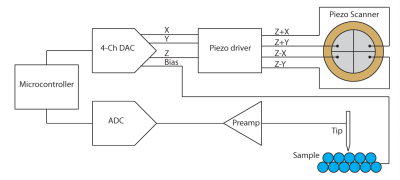

YouTuber [MechnicalRedPanda] has recreated a DIY STM hack we covered about ten years ago, updating it to be primarily 3D-printed, using modern electronics, making it much more accessible to many folks. This simple STM setup utilises a piezoelectric actuator constructed by deliberately cutting a piezo speaker into four quadrants. With individual drive wires attached to the four quadrants. [MechPanda] (re)discovered that piezoelectric ceramic materials are not big fans of soldering heat. Still, in the absence of ultrasonic welding equipment, he did manage to get some wires to take to the surface using low-temperature solder paste.

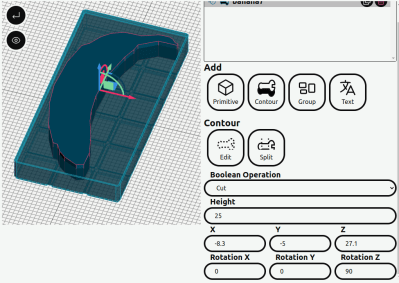

A makeshift probe holder was glued on the rear side of the speaker actuator, which was intended to take a super sharp needle-like piece of tungsten wire. Putting the wire in tension and cutting at a sharp angle makes it possible with many attempts to get some usable points. Usable, in this instance, means sharp down the atomic level. The sample platform, actuator mount and all the connecting parts are 3D-printed with PA-CF. This is necessary to achieve enough mechanical stability with normal room temperature fluctuations. Three precision screws are used to level the two platforms in a typical kinematic mount structure, which looks like the only hard-to-source component. A geared stepper motor attached to the probe platform is set up to allow the probe to be carefully advanced towards the sample surface. Continue reading “Building A 3D Printed Scanning Tunneling Microscope”