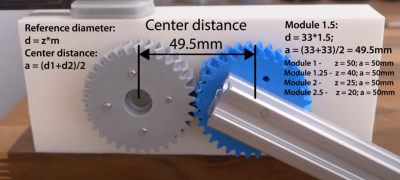

[How to Mechatronics] on YouTube endeavored to create a comprehensive guide comparing the various factors that affect the performance of 3D printed gears. Given the numerous variables involved, this is a challenging task, but it aims to shed light on the differences. The guide focuses on three types of gears: the spur gear with straight teeth parallel to the gear axis, the helical gear with teeth at an angle, and the herringbone gear, which combines two helical gear designs. Furthermore, the guide delves into how printing factors such as infill density impact strength, and it tests various materials, including PLA, carbon fiber PLA, ABS, PETG, ASA, and nylon, to determine the best options.

The spur gear is highly efficient due to the minimal contact path when the gears are engaged. However, the sudden contact mechanism, as the teeth engage, creates a high impulse load, which can negatively affect durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.

It’s worth noting that multiple teeth are involved in power transmission, with the gradual engagement and disengagement of the tooth being spread out over more teeth than the spur design. The downside is that there is a significant sideways force due to the inclined angle of the teeth, which must be considered in the enclosing structure and may require an additional bearing surface to handle it. Herringbone gears solve this problem by using two helical gears thrusting in opposite directions, cancelling out the force.

Continue reading “Studying The Finer Points Of 3D Printed Gears”