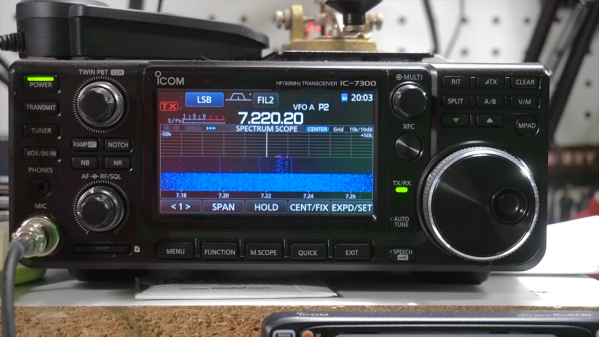

When the first radios and telegraph lines were put into service, essentially the only way to communicate was to use Morse code. The first transmitters had extremely inefficient designs by today’s standards, so this was more a practical limitation than a choice. As the technology evolved there became less and less reason to use Morse to communicate, but plenty of amateur radio operators still use this mode including [Kevin] aka [KB9RLW] who has built a circuit which can translate spoken Morse code into a broadcasted Morse radio signal.

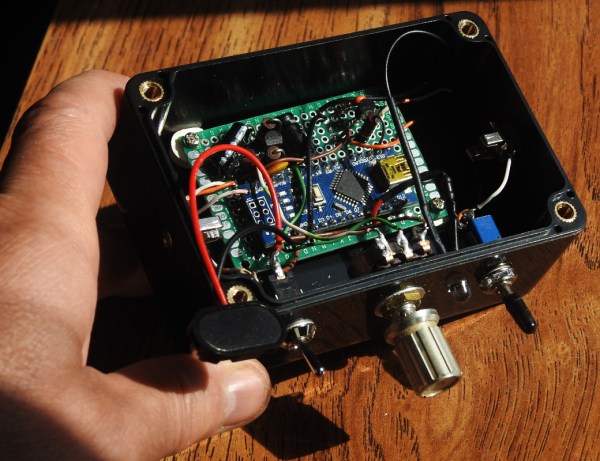

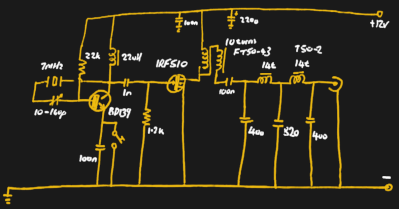

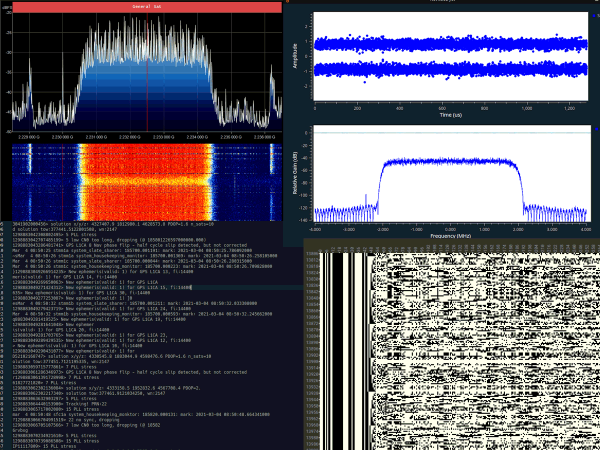

The circuit works by feeding the signal from a microphone into an Arduino. The Arduino listens for a certain threshold and keys the radio when it detects a word being spoken. Radio operators use the words “dit” and “dah” for dots and dashes respectively, and the Arduino isn’t really translating the words so much as it is sending a signal for the duration of however long each word takes to say. The software for the Arduino is provided on the project’s GitHub page as well, and uses a number of approaches to make sure the keyed signal is as clean as possible.

[Kevin] mentions that this device could be used by anyone who wishes to operate a radio in this mode who might have difficulty using a traditional Morse key and who doesn’t want to retrain their brain to use other available equipment like a puff straw or a foot key. The circuit is remarkably straightforward for what it does, and in the video below it seems [Kevin] is having a blast using it. If you’re still looking to learn to “speak” Morse code, though, take a look at this guide which goes into detail about it.

Thanks to [Dragan] for the tip!

Continue reading “Translating And Broadcasting Spoken Morse Code”