If many millions of years of evolution is good for anything, it is to develop microscopic structures that perform astounding tasks, such as the marvelous biology of insects. One of these structures are the ears of the lesser wax moth (Achroia grisella), whose mating behavior involves ultrasonic mating calls. These can attract the bats which hunt them, leading to these moths having evolved directional hearing that can pinpoint not only a potential mate, but also bat calling sound.

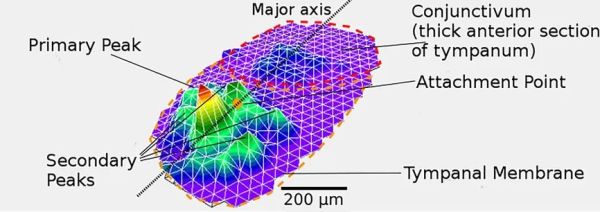

What’s most astounding about this is that these moths that only live about a week as an adult can perform auditory feats that we generally require an entire microphone array for, along with a lot of audio processing. The key that enables these moths to perform these feats lies in their eardrum, or tympanum. Rather than the taut, flat surface as with mammals, these feature intricate 3D structures along with pores that seem to perform much of the directional processing, and this is what researchers have been trying to replicate for a while, including a team of researchers at the University of Strathclyde.

To create these artificial tympanums, the researchers used a flexible hydrogel, with a piezoelectric material that converts the acoustic energy into electric signals, connected to electrical traces. The 3D features are printed on this, mixed with methanol that forms droplets inside the curing resin, before being expelled and leaving the desired pores. One limitation is that currently used printers have a limited resolution of about 200 micrometers, which doesn’t cover the full features of the insect’s tympanum.

Assuming this can be made to work, it could be used for everything from cochlear implants to anywhere else that has a great deal of audio processing that needs downsizing.

(Heading image: Mapping of the displacement of a tympanum of the lesser wax moth (Achroia grisella). (Credit: Andrew Reid) )