Here’s a classic “one thing led to another” car hack. [Alexandre Blin] wanted a reversing camera for his old Peugeot 207 and went down a rabbit hole which led him to do some extreme CAN bus reverse-engineering with Arduino and iOS. Buying an expensive bezel, a cheap HDMI display, an Arduino, a CAN bus shield, an iPod touch with a ghetto serial interface cable that didn’t work out, a HM-10 BLE module, an iPad 4S, the camera itself, and about a year and a half of working on it intermittently, he finally emerged poorer by about 275€, but victorious in a job well done. A company retrofit would not only have cost him a lot more, but would have deprived him of everything that he learned along the way.

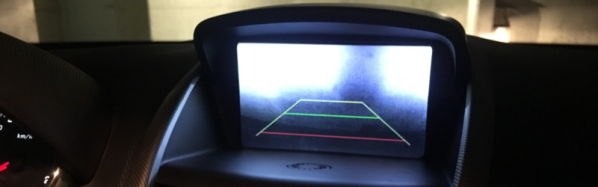

Adding the camera was the easiest part of the exercise when he found an after-market version specifically meant for his 207 model. The original non-graphical display had to make room for a new HDMI display and a fresh bezel, which cost him much more than the display. Besides displaying the camera image when reversing, the new display also needed to show all of the other entertainment system information. This couldn’t be obtained from the OBD-II port but the CAN bus looked promising, although he couldn’t find any details for his model initially. But with over 2.5 million of the 207’s on the road, it wasn’t long before [Alexandre] hit jackpot in a French University student project who used a 207 to study the CAN bus. The 207’s CAN bus system was sub-divided in to three separate buses and the “comfort” bus provided all the data he needed. To decode the CAN frames, he used an Arduino, a CAN bus shield and a python script to visualize the data, checking to see which frames changed when he performed certain functions — such as changing volume or putting the gear in reverse, for example.

Adding the camera was the easiest part of the exercise when he found an after-market version specifically meant for his 207 model. The original non-graphical display had to make room for a new HDMI display and a fresh bezel, which cost him much more than the display. Besides displaying the camera image when reversing, the new display also needed to show all of the other entertainment system information. This couldn’t be obtained from the OBD-II port but the CAN bus looked promising, although he couldn’t find any details for his model initially. But with over 2.5 million of the 207’s on the road, it wasn’t long before [Alexandre] hit jackpot in a French University student project who used a 207 to study the CAN bus. The 207’s CAN bus system was sub-divided in to three separate buses and the “comfort” bus provided all the data he needed. To decode the CAN frames, he used an Arduino, a CAN bus shield and a python script to visualize the data, checking to see which frames changed when he performed certain functions — such as changing volume or putting the gear in reverse, for example.

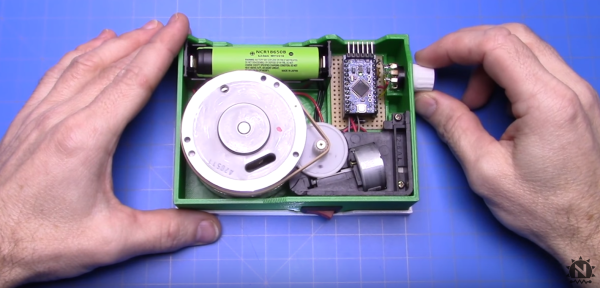

The Arduino could not drive the HDMI display directly, so he needed additional hardware to complete his hack. While a Raspberry Pi would have been ideal, [Alexandre] is an iOS developer so he naturally gravitated towards the Apple ecosystem. He connected an old iPod to the Arduino via a serial connection from the Dock port on the iPod. But using the Apple HDMI adapter to connect to the display broke the serial connection, so he had to put his thinking cap back on. This time, he used a HM-10 BLE module connected to the Arduino, and replaced the older iPod Touch (which didn’t support BLE) with a more modern iPhone 4S. Once he had all the bits and pieces working, it wasn’t too long before he could wrap up this long drawn upgrade, but the final result looks as good as a factory original. Check out the video after the break.

It’s great to read about these kinds of hacks where the hacker digs in his feet and doesn’t give up until it’s done and dusted. And thanks to his detailed post, and all the code shared on his GitHub repository, it should be easy to replicate this the second time around, for those looking to upgrade their old 207. And if you’re looking for inspiration, check out this great Homemade Subaru Head Unit Upgrade.

Continue reading “Reverse-Engineering The Peugeot 207’s CAN Bus” →

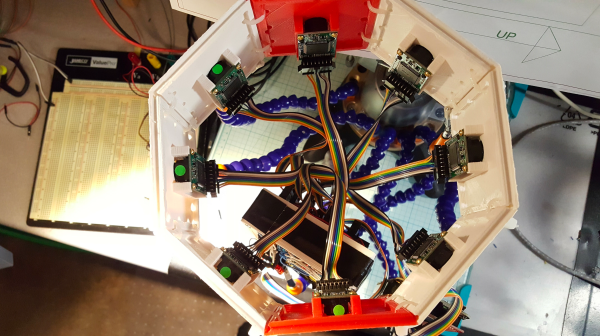

In the image to the right, [Mark] is testing out his software for getting the various cameras to work together. The banks of circles and the dots and lines connecting to them represent the computer’s best guess on how to seamlessly merge the images.

In the image to the right, [Mark] is testing out his software for getting the various cameras to work together. The banks of circles and the dots and lines connecting to them represent the computer’s best guess on how to seamlessly merge the images.

Adding the camera was the easiest part of the exercise when he found an after-market version specifically meant for his 207 model. The original non-graphical display had to make room for a new HDMI display and a fresh bezel, which cost him much more than the display. Besides displaying the camera image when reversing, the new display also needed to show all of the other entertainment system information. This couldn’t be obtained from the OBD-II port but the CAN bus looked promising, although he couldn’t find any details for his model initially. But with over 2.5 million of the 207’s on the road, it wasn’t long before [Alexandre] hit jackpot in a French University student project who used a 207 to study the CAN bus. The 207’s CAN bus system was sub-divided in to three separate buses and the “comfort” bus provided all the data he needed. To decode the CAN frames, he used an Arduino, a CAN bus shield and a python script to visualize the data, checking to see which frames changed when he performed certain functions — such as changing volume or putting the gear in reverse, for example.

Adding the camera was the easiest part of the exercise when he found an after-market version specifically meant for his 207 model. The original non-graphical display had to make room for a new HDMI display and a fresh bezel, which cost him much more than the display. Besides displaying the camera image when reversing, the new display also needed to show all of the other entertainment system information. This couldn’t be obtained from the OBD-II port but the CAN bus looked promising, although he couldn’t find any details for his model initially. But with over 2.5 million of the 207’s on the road, it wasn’t long before [Alexandre] hit jackpot in a French University student project who used a 207 to study the CAN bus. The 207’s CAN bus system was sub-divided in to three separate buses and the “comfort” bus provided all the data he needed. To decode the CAN frames, he used an Arduino, a CAN bus shield and a python script to visualize the data, checking to see which frames changed when he performed certain functions — such as changing volume or putting the gear in reverse, for example.