Every once in a while, you get your hands on a cool piece of hardware, and of course, it’s your first instinct to open it up and see how it works, right? Maybe see if it can be coaxed into doing just a little bit more than it says on the box? And so it was last Wednesday, when I was at the Embedded World trade fair, and stumbled on a cool touch display floating apparently in mid-air.

The display itself was a sort of focused Pepper’s Ghost illusion, reflected off of an expensive mirror made by Aska3D. I don’t know much more — I didn’t get to bring home one of the fancy glass plates — but it looked pretty good. But this display was interactive: you could touch the floating 2D projection as if it were actually there, and the software would respond. What was doing the touch response in mid-air? I’m a sucker for sensors, so I started asking questions and left with a small box of prototype Neonode zForce AIR sensor sticks to take apart.

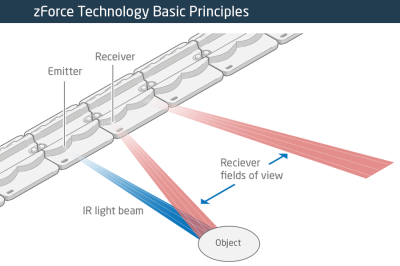

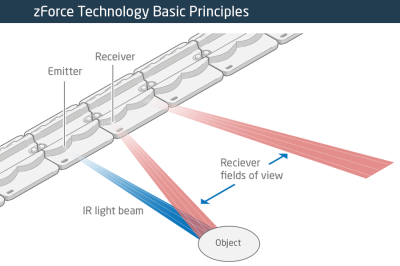

The zForce sensors are essentially an array of IR lasers and photodiodes with some lenses that limit their field of view. The IR light hits your finger and bounces back to the photodiodes on the bar. Because the photodiodes have a limited angle over which they respond, they can be used to triangulate the distance of the finger above the display. Scanning quickly among the IR lasers and noting which photodiodes receive a reflection can locate a few fingertips in a 2D space, which explained the interactive part of the floating display. With one of these sensors, you can add a 2D touch surface to anything. It’s like an invisible laser harp that can also sense distance.

The zForce sensors are essentially an array of IR lasers and photodiodes with some lenses that limit their field of view. The IR light hits your finger and bounces back to the photodiodes on the bar. Because the photodiodes have a limited angle over which they respond, they can be used to triangulate the distance of the finger above the display. Scanning quickly among the IR lasers and noting which photodiodes receive a reflection can locate a few fingertips in a 2D space, which explained the interactive part of the floating display. With one of these sensors, you can add a 2D touch surface to anything. It’s like an invisible laser harp that can also sense distance.

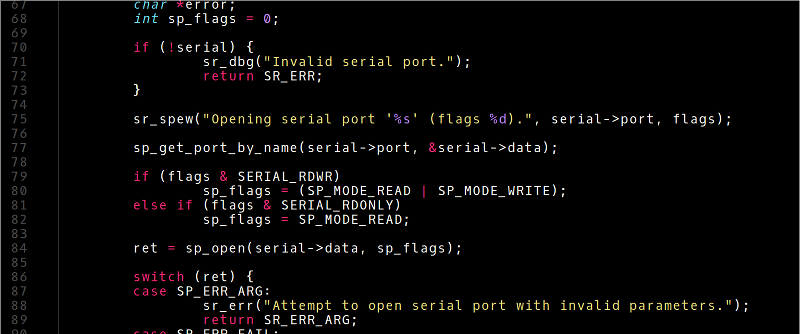

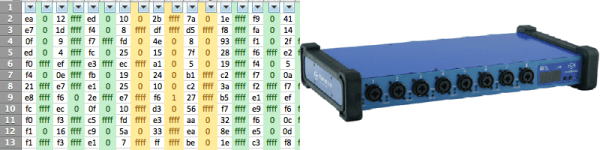

The intended purpose is fingertip detection, and that’s what the firmware is good at, but it must also be the case that it could detect the shape of arbitrary (concave) objects within its range, and that was going to be my hack. I got 90% of the way there in one night, thanks to affordable tools and free software that every hardware hacker should have in their toolbox. So read on for the unfortunate destruction of nice hardware, a tour through some useful command-line hardware-hacking tools, and gratuitous creation of animations from sniffed SPI-like data pulled off of some test points.

Continue reading “What’s Inside A Neonode Laser Sensor?” →

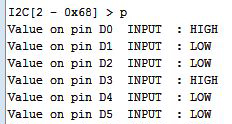

hile Arduino and its libraries are the quickest way to interface with a sensor and blink an LED, sometimes you shouldn’t have to write and compile code to do something exceptionally simple. [Oliver] realized most of the overly simple functions of a microcontroller could be done from a command line running on that microcontroller and

hile Arduino and its libraries are the quickest way to interface with a sensor and blink an LED, sometimes you shouldn’t have to write and compile code to do something exceptionally simple. [Oliver] realized most of the overly simple functions of a microcontroller could be done from a command line running on that microcontroller and