Some people build their own computer to play games, while others play games to build their own computer. Minecraft is the prime candidate for the latter, and while you can certainly arrange the blocks to make them look like a computer, we’re of course talking about replicating the actual functionality of a CPU or parts thereof, and/or external components within the game. Many such creations have spawned in the decade since the first Minecraft-built ALU surfaced, and [Rockfarmor] built a 64-bit specimen to add to that list — and made a video to showcase it.

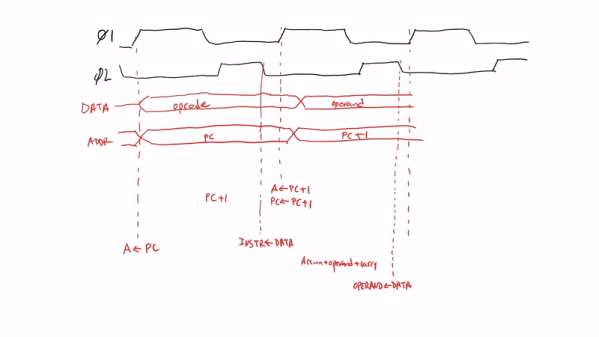

Instead of emulating a common architecture, [Rockfarmor] went for a more home-made approach, and re-used the architecture from an old school assignment (in Swedish) as basis. The result is a simple yet fully functional 64-bit CPU with 32 registers, 32kB main memory and a separate 16kB stack. The instruction set mostly contains ALU and branching operations, but also a few special opcodes to control an additional 64×64 pixel blocks, 64-color display — including drawing circles, lines, and color fills.

More details on the architecture can be found in its documentation and in an older video (with subpar audio circumstances unfortunately). An additional time-lapse video of the initial build is also available, and you will find all of them after break. To simplify development, [Rockfarmor] also wrote a desktop app to program the computer in assembly and upload it straight to the Minecraft version.

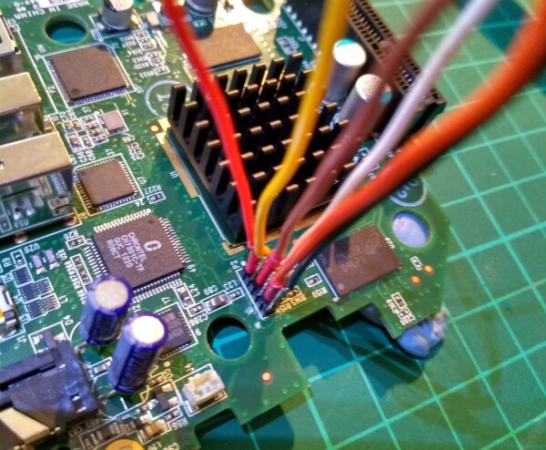

As with all computers built in Minecraft, the driving force is redstone, which essentially allows circuit design within the game, and [Rockfarmor]’s is no difference here. He also uses command blocks to avoid the laboriously and slow “wiring” required otherwise, turning it more into a “wireless redstone” circuit.

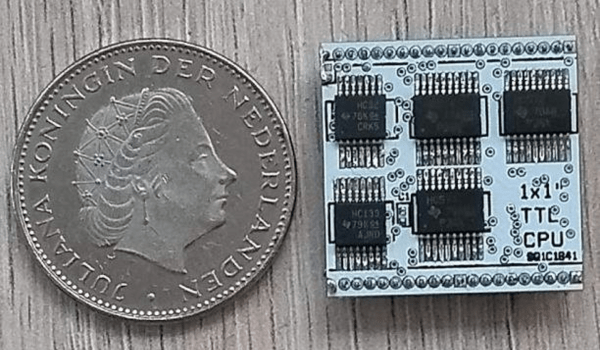

No doubt, purists will consider this cheating, but another angle would be to see it as Moore’s Law applied to Minecraft computers, considering the computer’s size and speed compared to the first Minecraft ALU. Or maybe as the equivalent of microcode in real-world CPUs? Or then, maybe we should just accept and embrace different options and preferences.

Continue reading “64-bit And A Display: Minecraft Computers 10 Years Later”