Right-to-repair has been a hot-button topic lately, with everyone from consumers to farmers pretty much united behind the idea that owning an item should come with a plausible path to getting it fixed if it breaks, or more specifically, that you shouldn’t be subject to prosecution for trying to repair your widget. Not everyone likes right-to-repair, of course — plenty of big corporations want to keep you from getting up close and personal with their intellectual property. Strangely enough, their ranks are now apparently joined by the Church of Scientology, who through a media outfit in charge of the accumulated works of Church founder L. Ron Hubbard are arguing against exemptions to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) that make self-repair possible for certain classes of devices. They apparently want the exemption amended to not allow self-repair of any “software-powered devices that can only be purchased by someone with particular qualifications or training or that use software ‘governed by a license agreement negotiated and executed’ before purchase.

emergency alert system8 Articles

Fox Fined For Using EAS Tone In Football Ad

The Boy Who Cried Wolf is a simple parable that teaches children the fatal risk of raising a false alarm. To do so is to risk one’s life when raising the alarm about a real emergency that may go duly ignored.

Today, we rarely fear wolves, and we don’t worry about them eating us, our sheep, or our children. Instead, we worry about bigger threats, like incoming nuclear weapons, tornadoes, and earthquakes. We’ve built systems to warn us of these calamities, and authorities take a very dim view of those who misuse these alarms. Fox did just that in a recent broadcast, using a designated alarm tone for an advert. This quickly drew the attention of the Federal Communication Commission.

Continue reading “Fox Fined For Using EAS Tone In Football Ad”

Hackaday Links: August 21, 2022

As side-channel attacks go, it’s one of the weirder ones we’ve heard of. But the tech news was filled with stories this week about how Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” is actually a form of cyberattack. It sounds a little hinky, but apparently this is an old vulnerability, as it was first noticed back in the days when laptops commonly had 5400-RPM hard drives. The vulnerability surfaced when the video for that particular ditty was played on a laptop, which would promptly crash. Nearby laptops of the same kind would also be affected, suggesting that whatever was crashing the machine wasn’t software related. As it turns out, some frequencies in the song were causing resonant vibrations in the drive. It’s not clear if anyone at the time asked the important questions, like exactly which part of the song was responsible or what the failure mode was on the drive. We’ll just take a guess and say that it was the drive heads popping and locking.

Hackaday Links: August 18, 2019

To the surprise of nobody with the slightest bit of technical intuition or just plain common sense, the world’s first solar roadway has proven to be a complete failure. The road, covering one lane and stretching all of 1,000 meters across the Normandy countryside, was installed in 2016 to great fanfare and with the goal of powering the streetlights in the town of Tourouvre. It didn’t even come close, producing less than half of its predicted power, due in part to the accumulation of leaves on the road every fall and the fact that Normandy only enjoys about 44 days of strong sunshine per year. Who could have foreseen such a thing? Dave Jones at EEVBlog has been all over the solar freakin’ roadways fiasco for years, and he’s predictably tickled pink by this announcement.

I’m not going to admit to being the kid in grade school who got bored in class and regularly filled pages of my notebook with all the binary numbers between 0 and wherever I ran out of room – or got caught. But this entirely mechanical binary number trainer really resonates with me nonetheless. @MattBlaze came up with the 3D-printed widget and showed it off at DEF CON 27. Each two-sided card has an arm that flops down and overlaps onto the more significant bit card to the left, which acts as a carry flag. It clearly needs a little tune-up, but the idea is great and something like this would be a fun way to teach kids about binary numbers. And save notebook paper.

Is that a robot in your running shorts or are you just sporting an assistive exosuit? In yet another example of how exoskeletons are becoming mainstream, researchers at Harvard have developed a soft “exoshort” to assist walkers and runners. These are not a hard exoskeleton in the traditional way; rather, these are basically running short with Bowden cable actuators added to them. Servos pull the cables when the thigh muscles contract, adding to their force and acting as an aid to the user whether walking or running. In tests the exoshorts resulted in a 9% decrease in the amount of effort needed to walk; that might not sound like much, but a soldier walking 9% further on the same number of input calories or carrying 9% more load could be a big deal.

In the “Running Afoul of the FCC” department, we found two stories of interest. The first involves Jimmy Kimmel’s misuse of the Emergency Alert System tones in an October 2018 skit. The stunt resulted in a $395,000 fine for ABC, as well as hefty fines for two other shows that managed to include the distinctive EAS tones in their broadcasts, showing that the FCC takes very seriously indeed the integrity of a system designed to warn people of their approaching doom.

The second story from the regulatory world is of a land mobile radio company in New Jersey slapped with a cease and desist order by the FCC for programming mobile radios to use the wrong frequency. The story (via r/amateurradio) came to light when someone reported interference from a car service’s mobile radios; subsequent investigation showed that someone had programmed the radios to transmit on 154.8025 MHz, which is 5 MHz below the service’s assigned frequency. It’s pretty clear that the tech who programmed the radio either fat-fingered it or misread a “9” as a “4”, and it’s likely that there was no criminal intent. The FCC probably realized this and didn’t levy a fine, but they did send a message loud and clear, not only to the radio vendor but to anyone looking to work frequencies they’re not licensed for.

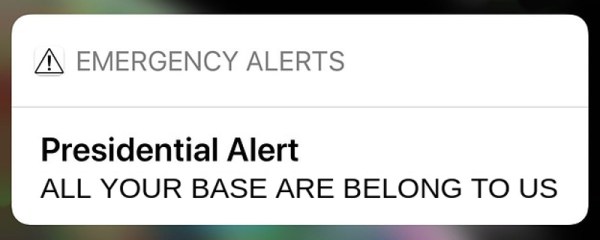

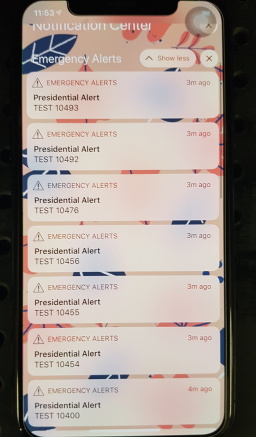

Impersonate The President With Consumer-Grade SDR

In April of 2018, the Federal Emergency Management Agency sent out the very first “Presidential Alert”, a new class of emergency notification that could be pushed out in addition to the weather and missing child messages that most users were already familiar with. But while those other messages are localized in nature, Presidential Alerts are intended as a way for the Government to reach essentially every mobile phone in the country. But what if the next Presidential Alert that pops up on your phone was actually sent from somebody with a Software Defined Radio?

According to research recently released by a team from the University of Colorado Boulder, it’s not as far-fetched a scenario as you might think. In fact, given what they found about how the Commercial Mobile Alert Service (CMAS) works, there might not be a whole lot we can even do to prevent it. The system was designed to push out these messages in the most expedient and reliable way possible, which meant that niceties like authentication had to take a backseat.

The thirteen page report, which was presented at MobiSys 2019 in Seoul, details their findings on CMAS as well as their successful efforts to send spoofed Presidential Alerts to phones of various makes and models. The team used a BladeRF 2.0 and USRP B210 to perform their mock attacks, and even a commercially available LTE femtocell with modified software. Everything was performed within a Faraday cage to prevent fake messages from reaching the outside world.

The thirteen page report, which was presented at MobiSys 2019 in Seoul, details their findings on CMAS as well as their successful efforts to send spoofed Presidential Alerts to phones of various makes and models. The team used a BladeRF 2.0 and USRP B210 to perform their mock attacks, and even a commercially available LTE femtocell with modified software. Everything was performed within a Faraday cage to prevent fake messages from reaching the outside world.

So how does the attack work? To make a long story short, the team found that phones will accept CMAS messages even if they are not currently authenticated with a cell tower. So the first phase of the attack is to spoof a cell tower that provides a stronger signal than the real ones in the area; not very difficult in an enclosed space. When the phone sees the stronger “tower” it will attempt, but ultimately fail, to authenticate with it. After a few retries, it will give up and switch to a valid tower.

This negotiation takes around 45 seconds to complete, which gives the attacker a window of opportunity to send the fake alerts. The team says one CMAS message can be sent every 160 milliseconds, so there’s plenty of time to flood the victim’s phone with hundreds of unblockable phony messages.

The attack is possible because the system was intentionally designed to maximize the likelihood that users would receive the message. Rather than risk users missing a Presidential Alert because their phones were negotiating between different towers at the time, the decision was made to just push them through regardless. The paper concludes that one of the best ways to mitigate this attack would be to implement some kind of digital signature check in the phone’s operating system before the message gets displayed to the user. The phone might not be able to refuse the message itself, but it can at least ascertain it’s authentic before showing it to the user.

All of the team’s findings have been passed on to the appropriate Government agencies and manufacturers, but it will likely be some time before we find out what (if any) changes come from this research. Considering the cost of equipment that can spoof cell networks has dropped like a rock over the last few years, we’re hoping all the players can agree on a software fix before we start drowning in Presidential Spam.

You’ll Really Want An “Undo” Button When You Accidentally Send A Ballistic Missile Warning

Hawaiians started their weekend with quite a fright, waking up Saturday morning to a ballistic missile alert that turned out to be a false alarm. In between the public anger, profuse apologies from officials, and geopolitical commentary, it might be hard to find some information for the more technical-minded. For this audience, The Atlantic has compiled a brief history of infrastructure behind emergency alerts.

As a system intended to announce life-critical information when seconds count, all information on the system is prepared ahead of time for immediate delivery. As a large hodgepodge linking together multiple government IT systems, there’s no surprise it is unwieldy to use. These two aspects collided Saturday morning: there was no prepared “Sorry, false alarm” retraction message so one had to be built from scratch using specialized equipment, uploaded across systems, and broadcast 38 minutes after the initial false alarm. In the context of government bureaucracy, that was really fast and must have required hacking through red tape behind the scenes.

However, a single person’s mistake causing such chaos and requiring that much time to correct is unacceptable. This episode has already prompted a lot of questions whose answers will hopefully improve the alert system for everyone’s benefit. At the very least, a retraction is now part of the list of prepared messages. But we’ve also attracted attention of malicious hackers to this system with obvious problems in design, in implementation, and also has access to emergency broadcast channels. The system needs to be fixed before any more chaotic false alarms – either accidental or malicious – erode its credibility.

We’ve covered both the cold-war era CONELRAD and the more recent Emergency Broadcast System. We’ve also seen Dallas’ tornado siren warning system hacked. They weren’t the first, they won’t be the last.

(Image: Test launch of an unarmed Minuteman III ICBM via US Air Force.)

Radio Apocalypse: The Emergency Broadcast System

Some sounds are capable of evoking instant terror. It might be the shriek of a mountain lion, or a sudden clap of thunder. Whatever your trigger sound, it instantly stimulates something deep in the lizard brain that says: get ready, danger is at hand.

For my part, you can’t get much scarier than the instantly recognizable two-tone alert signal (audio link warning) from the Emergency Broadcast System (EBS). For anyone who grew up watching TV in the 60s and 70s in the US, it was something you heard on at least a weekly basis, with that awful tone followed by a grave announcement that “the broadcasters of your area, in voluntary cooperation with the FCC and other authorities, have developed this system to keep you informed in the event of an emergency.” It was a constant reminder that white-hot death could rain from the sky at any moment, and the idea that the last thing you may ever hear was that tone was sickening.

While I no longer have a five-year-old’s response to that sound, it’s still a powerful reminder of a scary time. And the fact that it’s still in use today, at least partially, seems like a good reason to look at the EBS in a little more depth, and find out the story behind the soundtrack of the end of the world.

Continue reading “Radio Apocalypse: The Emergency Broadcast System”