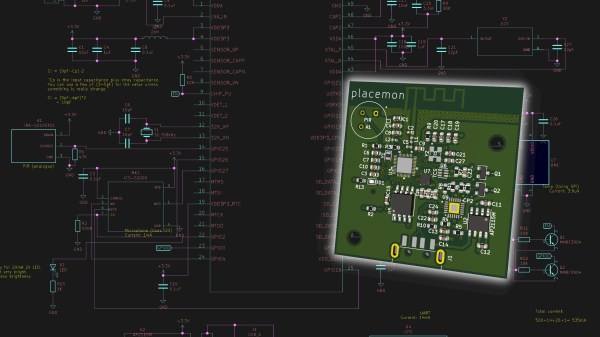

No, no, at first we thought it was a Pokemon too, but Placemon monitors your place, your home, your domicile. Instead of a purpose-built device, like a CO detector or a burglar alarm, this is a generalized monitor that streams data to a central processor where machine learning algorithms notify you if something is awry. In a way, it is like a guard dog who texts you if your place is unusually cold, on fire, unlawfully occupied, or underwater.

[anfractuosity] is trying to make a hacker-friendly version based on inspiration from a scientific paper about general-purpose sensing, which will have less expensive components but will lose accuracy. For example, the article suggests thermopile arrays, like low-resolution heat-vision, but Placemon will have a thermometer, which seems like a prudent starting place.

The PCB is ready to start collecting sound, temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, illumination, and passive IR then report that telemetry via an onboard ESP32 using Wifi. A box utilizing Tensorflow receives the data from any number of locations and is training to recognize a few everyday household events’ sensor signatures. Training starts with events that are easy to repeat, like kitchen sounds and appliance operations. From there, [anfractuosity] hopes that he will be versed enough to teach it new sounds, so if a pet gets added to the mix, it doesn’t assume there is an avalanche every time Fluffy needs to go to the bathroom.

We have another outstanding example of sensing household events without directly interfacing with an appliance, and bringing a sensor suite to your car might be up your alley.