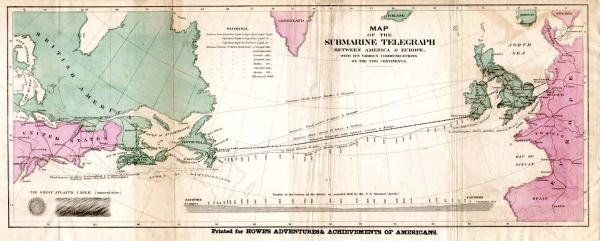

Code obfuscation has been around for a long time. The obfuscated C contest first ran way back in 1984, but there are examples of natural language obfuscation from way earlier in history. Namely Cockney rhyming slang, like saying “Lady from Bristol” instead of “pistol” or “lump of lead” instead of “head”. It’s speculated that Cockney was originally used to allow the criminal class to have conversations without tipping off police.

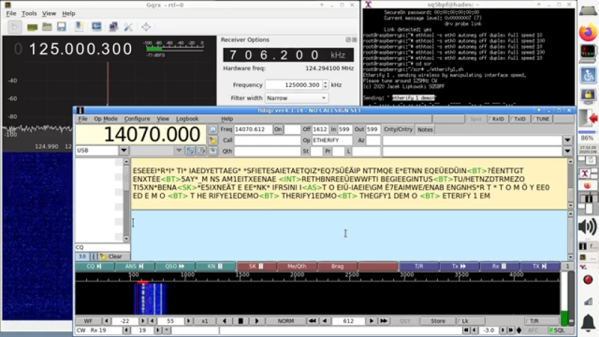

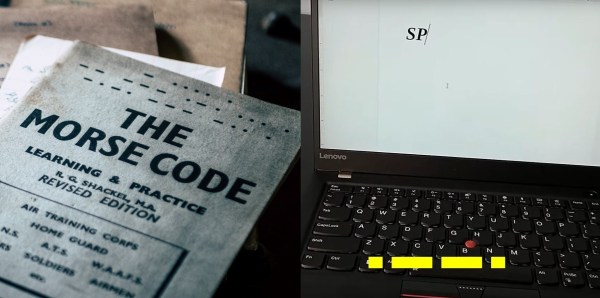

Code obfuscation in malware serves a similar purpose — hiding from security devices and applications. There are known code snippets and blacklisted IP addresses that anti-malware software scans for. If that known bad code can be successfully obfuscated, it can avoid detection. This is a bit of a constant game of cat-and-mouse, as the deobfuscation code itself eventually makes the blacklist. This leads to new obfuscation techniques, sometimes quite off the wall. Well this week, I found a humdinger of an oddball approach. Morse Code.

Yep, dots and dashes. The whole attack goes like this. You receive an email, claiming to be an invoice. It’s a .xlsx.hTML file. If you don’t notice the odd file extension, and actually let it open, you’re treated to a web page. The source of that page is a very minimal JS script that consists of a morse code decoder, and a payload encoded in Morse. In this case, the payload is simply a pair of external scripts that ask for an Office 365 login. The novel aspect of this is definitely the Morse Code. Yes, our own [Danie] covered this earlier this week, but it was too good not to mention here. Continue reading “This Week In Security: Morse Code Malware, Literal And Figurative Watering Holes, And More”