Quietly released and speedily buried by Parliamentary wrangles over Brexit is the news that Sussex Police have exhausted all lines of inquiry into the widely publicised drone sighting reports that caused London’s Gatwick Airport to be closed for several days last December. The county’s rozzers have ruled out 96 ‘people of interest’ and combed through 129 separate reports of drone activity, but admit that they are no closer to feeling any miscreant collars. There is no mention of either their claims at the time to have found drone wreckage, their earlier admissions that sightings might have been of police drones, or even that there might have been no drone involved at all.

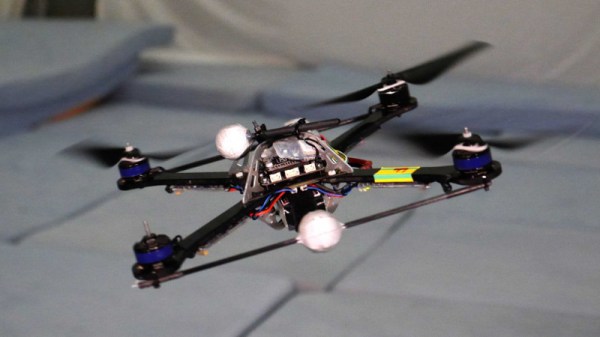

Regular readers will know that we have reported extensively the sorry saga of official reactions to drone incidents, because we believe that major failings in reporting and investigation will accumulate to have an adverse effect on those many people in our community who fly multi-rotors. In today’s BBC report for example there is the assertion that 109 of the drone sightings came from “‘credible witnesses’ including a pilot and airport police” which while it sounds reassuring is we believe a dangerous route to follow because it implies that the quality of evidence is less important than its source. It is crucial to understand that multi-rotors are still a technology with which the vast majority of the population are still unfamiliar, and simply because a witness is a police officer or a pilot does not make them a drone expert whose evidence is above scrutiny.

Whichever stand you take on the drone sightings at Gatwick and in other places it is clear that Sussex Police do not emerge from this smelling of roses and that their investigation has been chaotic and inept from the start. We believe that there should be a public inquiry into the whole mess, so that those embarrassing parts of it which they and other agencies are so anxious to quietly forget can be subjected to scrutiny. We do not however expect this to happen any time soon.

Keystone Kops header image: Mack Sennett Studios [Public domain].