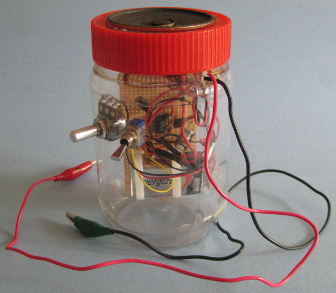

Sometimes the best builds aren’t anything new, but rather combining two well-developed hacks. [Marc] was familiar with RTL-SDR, the $30 USB TV tuner come software defined radio, but was surprised no one had yet combined this cheap radio dongle with the ability to transmit radio from a Raspberry Pi. [Marc] combined these two builds and came up with the cheapest portable radio modem for the Raspberry Pi.

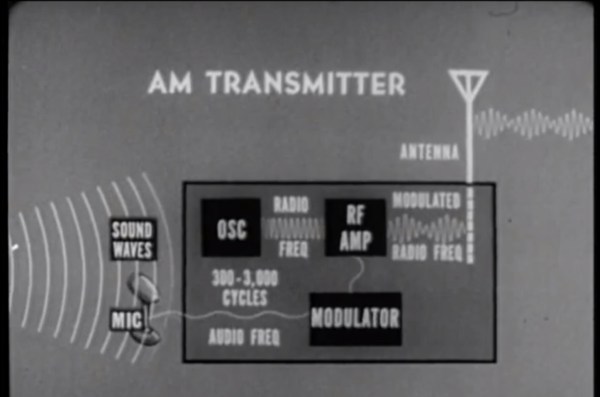

Turning the Raspi into a transmitter isn’t really that hard; it only requires a 20cm wire inserted into a GPIO pin, then toggling this pin at about 100 MHz. This resulting signal can be picked up fifty meters away, and through walls, even.

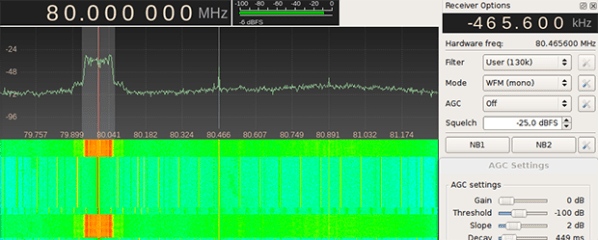

[Marc] combined this radio transmitter with minimodem, a program that generates audio modem tones at the required baud rate. Data is encoded in this audio stream, sent over the air, and decoded again with an RTL-SDR dongle.

It’s nothing new, per se, but if you’re looking for a short-range, low-bandwidth wireless connection between a computer and a Raspberry Pi, this is most certainly the easiest and cheapest method.