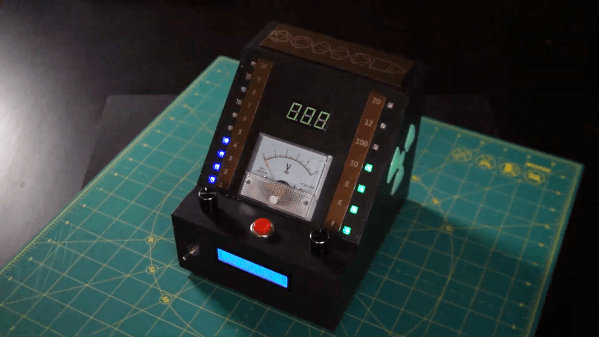

While we often get a detailed backstory of the projects we cover here at Hackaday, sometimes the genesis of a build is a bit of a mystery. Take [maurycyz]’s radiation survey meter modifications, for instance; we’re not sure why such a thing is needed, but we’re pretty glad we stumbled across it.

To be fair, [maurycyz] does give us a hint of what’s going on here by choosing the classic Ludlum Model 3 to modify. Built like a battleship, these meters would be great for field prospecting except that the standard G-M tube isn’t sensitive to gamma rays, the only kind of radiation likely not to be attenuated by soil. A better choice is a scintillation tube, but those greatly increase the background readings, making it hard to tease a signal from the noise.

To get around this problem and make rockhounding a little more enjoyable, [maurycyz] added a little digital magic to the mostly analog Ludlum. An AVR128 microcontroller taps into the stream of events the meter measures via the scintillation tube, and a little code subtracts the background radiation from the current count rate, translating the difference into an audible tone. This keeps [maurycyz]’s eyes on the rocks rather than on the meter needle, and makes it easier to find weakly radioactive or deeply buried specimens.

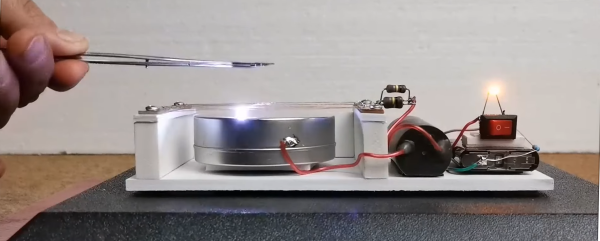

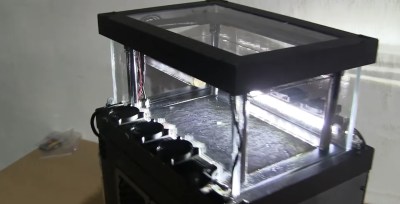

If you’re not ready to make the leap to a commercial survey meter, or if you just want to roll your own, we’ve got plenty of examples to choose from, from minimalist to cyberpunkish.