We all make mistakes, and there’s no shame in having to bodge a printed circuit board to fix a mistake. Most of us are content with cutting a trace or two with an Xacto or adding a bit of jumper wire to make the circuit work. Very few of us, however, will decide to literally do our bodges inside the PCB itself.

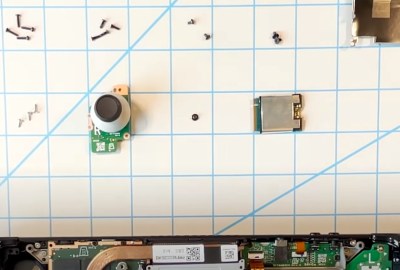

The story is that [Andrew Zonenberg] was asked to pitch in debugging some incredibly small PCBs for a prototype dev board that plugs directly into a USB jack. The six-layer boards are very dense, with a forest of blind vias. The Twitter thread details the debugging process, which ended up finding a blind via on layer two shorted to a power rail, and another via shorted to ground. It also has some beautiful shots of [Andrew]’s “mechanical tomography” method of visualizing layers by slowly grinding down the surface of the board.

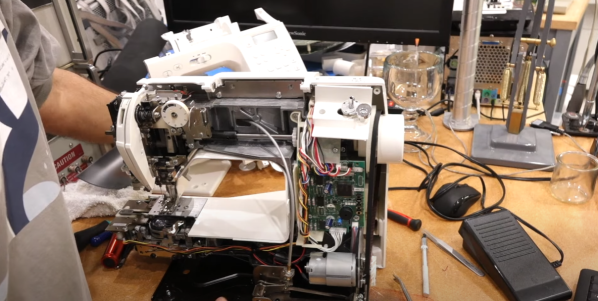

[Andrew] has only tackled one of the bodges at the time of writing, but it has to be seen to be believed. It started with milling away the PCB to get access to the blind via using a ridiculously small end mill. The cavity [Andrew] milled ended up being only about 480 μm by 600 μm and only went partially through a 0.8-mm thick board, but it was enough to resolve the internal short and add an internal bodge to fix a trace that was damaged during milling. The cavity was then filled up with epoxy resin to stabilize the repair.

This kind of debugging and repair skill just boggles the mind. It reminds us a bit of these internal chip-soldering repairs, but taken to another level entirely. We can’t wait to see what the second repair looks like, and whether the prototype for this dev board can be salvaged.

Thanks to [esclear] for the heads up on this one.