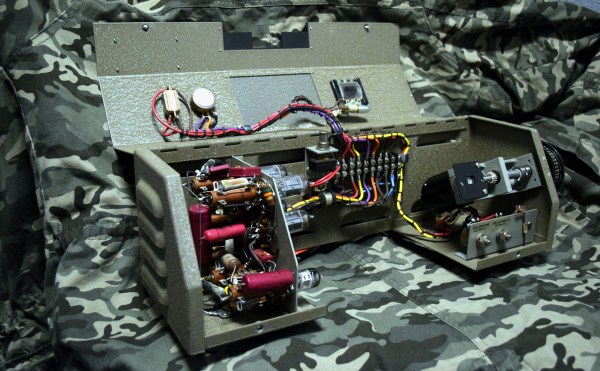

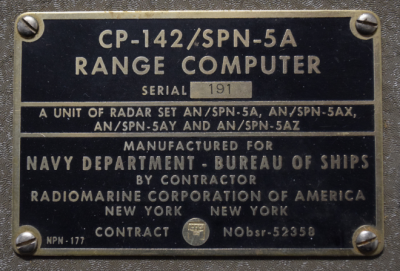

As some of my previous work here at Hackaday will attest to, I’m a big fan of World War II technology. Something about going in with wooden airplanes and leaving with jet fighters and space capable rockets has always captivated me. So when one of my lovingly crafted eBay alerts was triggered by something claiming to be a “Navy WWII Range Computer”, it’s safe to say I was interested.

Not to say I had any idea of what the thing was, mind you. I only knew it looked old and I had to have it. While I eagerly awaited the device to arrive at my doorstep, I tried to do some research on it and came up pretty much empty-handed. As you might imagine, a lot of the technical information for hardware that was developed in the 1940’s hasn’t quite made it to the Internet. Somebody was selling a technical manual that potentially would have covered the function of this device for $100 on another site, but I thought that might be a bit excessive. Besides, where’s the fun in that?

Not to say I had any idea of what the thing was, mind you. I only knew it looked old and I had to have it. While I eagerly awaited the device to arrive at my doorstep, I tried to do some research on it and came up pretty much empty-handed. As you might imagine, a lot of the technical information for hardware that was developed in the 1940’s hasn’t quite made it to the Internet. Somebody was selling a technical manual that potentially would have covered the function of this device for $100 on another site, but I thought that might be a bit excessive. Besides, where’s the fun in that?

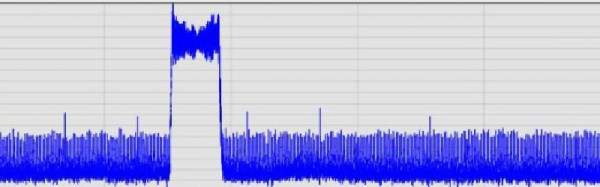

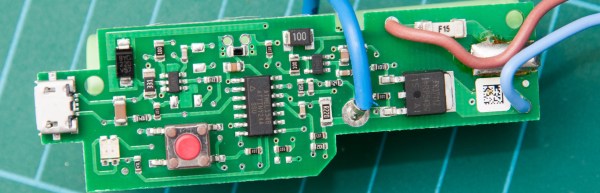

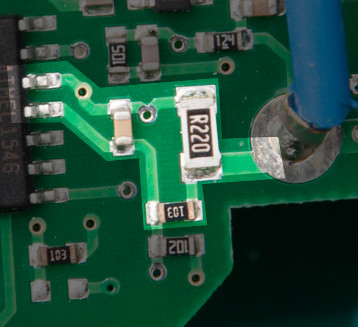

I decided to try to decipher what this device does by a careful examination of the hardware, consultation of what little technical data I could pull up on its individual components, and some modern gear. In the end I think I have a good idea of how it works, but I’d certainly love to hear if there’s anyone out there who might have actually worked with hardware like this and could fill in any blanks.