We’ve been recently looking into USB 2.0 – the ubiquitous point-to-point communications standard. USB 2 is completely different from USB 3, the blue-connector next-generation USB standard. For instance, USB 2 is a full-duplex pseudo-differential bus, and it’s not AC-coupled. This makes USB2 notoriously difficult to galvanically isolate, as opposed to USB 3. On the other hand, USB 2 is a lot easier to incorporate into your projects. And perhaps the best way to do so is to implement a USB hub.

USB 2 hubs are, by now, omnipresent. it doesn’t cost much to add to your board, and you truly have tons of options. The standard option is 4-port hubs – one uplink port to your host, four downlink ports to your devices. If you only have two or three devices, you might be tempted to look for a hub IC with a lower amount of ports, but it’s not worth bothering – just use a 4-port chip, and stock up on them.

What about 7-port chips? You will see those every now and then – but take a close look at the datasheet. Some of them will be two 4-port chips inside a single package, with four of the ports bottlenecked compared to the three other ports – watch out! Desktop 7-port hubs are basically guaranteed to use two 4-port ICs, too, so, again, watch out for bottlenecks. lsusb -t will help you determine the hub’s structure in case you don’t want to crack its case open, thankfully.

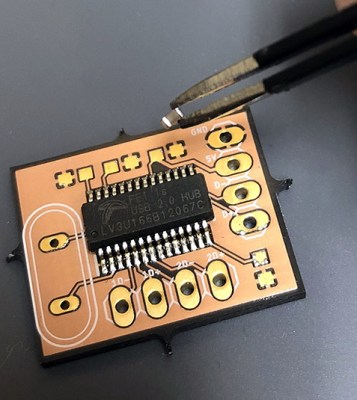

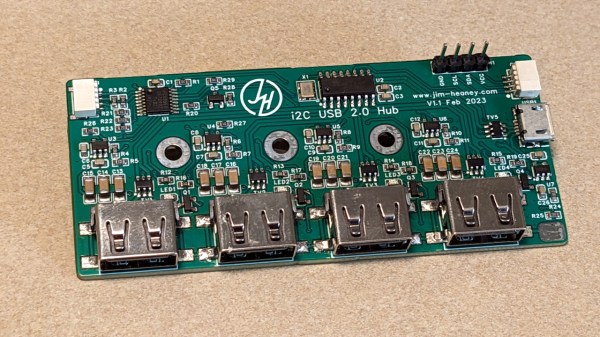

Recommendations? I use SL2.1 chips – they’re available in an SO16 package, very unproblematic, to-the-point pinout and easily hand-solderable. CH334 is a close contender, but watch out because there are different variants of this chip that differ by both package and pinout, so if you’re buying a chip with a certain letter, you will want to stick to it. Not just that, be careful – different variants run out at different rates, so if you lock yourself into a CH334 variant, consider stocking up on it. Continue reading “Ubiquitous Successful Bus: Hacking USB 2 Hubs”

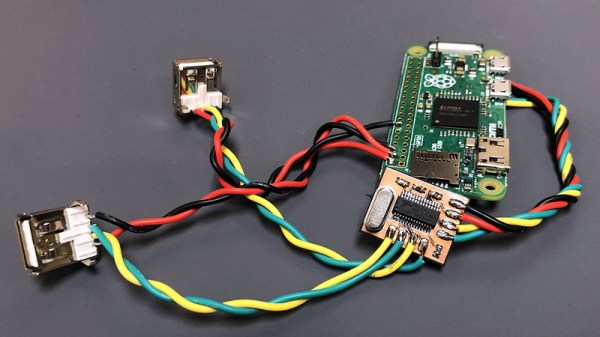

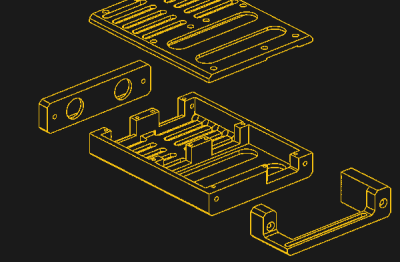

The modified USB hub is housed in a laser-cut enclosure with plenty of space to hook up a variety of USB devices. The touchscreen neatly fits just above [Matt]’s keyboard; this setup was inspired by head-down displays used in aircraft which similarly use a small additional screen for peripheral functions.

The modified USB hub is housed in a laser-cut enclosure with plenty of space to hook up a variety of USB devices. The touchscreen neatly fits just above [Matt]’s keyboard; this setup was inspired by head-down displays used in aircraft which similarly use a small additional screen for peripheral functions.