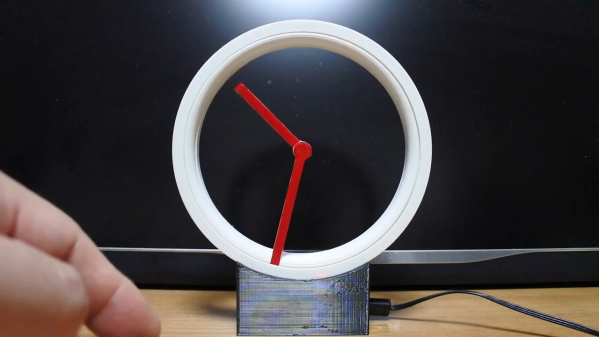

We love projects that make you do a double-take when you first see them. It’s always fun to think you see one thing, but then slowly realize everything is not quite what you expected. And this faceless analog clock is very much one of those projects.

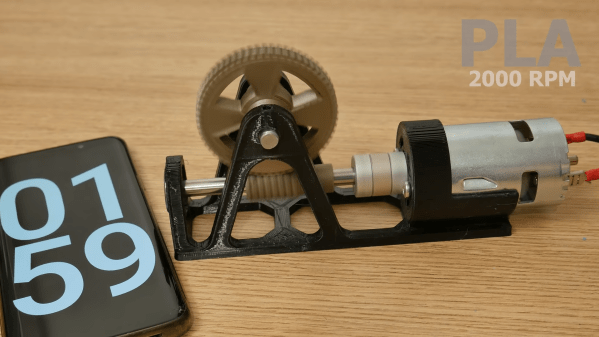

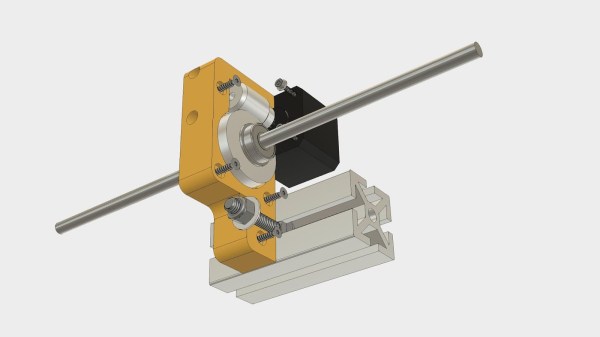

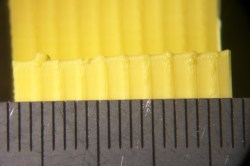

When we first saw [Shinsaku Hiura]’s “Hollow Clock 4,” we assumed the trick to making it look like the hands were floating in space would rely on the judicious use of clear acrylic. But no, this clock is truly faceless — you could easily stick a finger from front to back. The illusion is achieved by connecting the minute hand to the rim of the clock, and rotating the whole outer circumference through a compact 3D printed gear train. It’s a very clever mechanism, and it’s clear that it took a lot of work to optimize everything so that the whole look of the clock is sleek and modern.

But what about the hour hand? That’s just connected to the end of the minute hand at the center of the clock’s virtual face, so how does that work? As it is with most things that appear to be magical, the answer is magnets. The outer rim of the clock actually has another ring, this one containing a pair of neodymium magnets. They attract another magnet located in the very end of the hour hand, dragging it along as the hour ring rotates. The video below shows off the secrets, and it gives you some idea of how much work went into this clock.

We’re used to seeing unique and fun timepieces and other gadgets from [Shinsaku Hiura] — this up-flipping clock comes to mind, as does this custom RPN calculator — but this project is clearly a step beyond.

Continue reading “Faceless Clock Makes You Think Twice About How It Works”