While the polygraph is colloquially associated with pseudoscientific lie detector tests, the actual invention of the first polygraph was designed to mechanically duplicate the pen strokes of someone writing. Famously, a polygraph was used by former US President Thomas Jefferson in his “modern office”, a replica of which still sits in the Smithsonian museum. Few of us have a need for a pen-based polygraph anymore, but inspiration from the centuries-old invention can still be gleaned from the machine, like in this 3D printer which can output four identical prints at once.

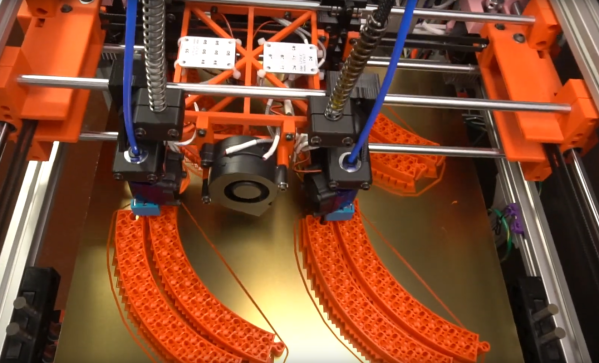

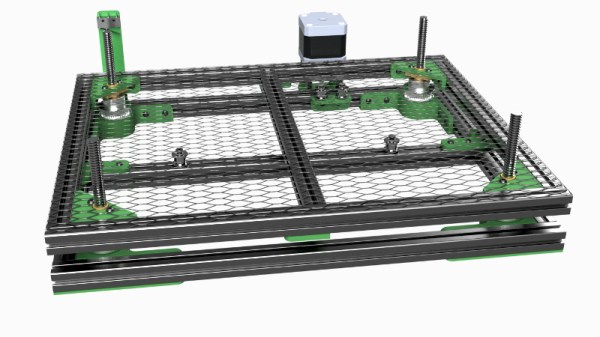

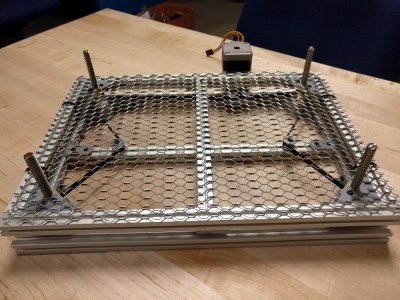

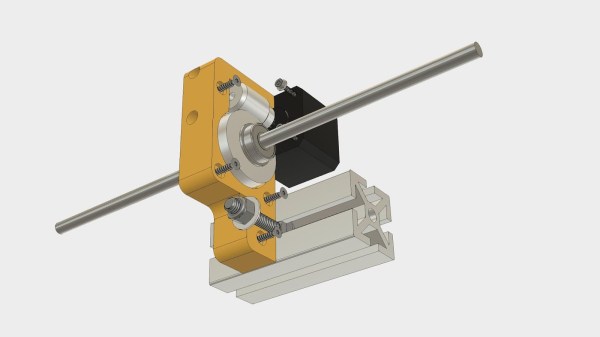

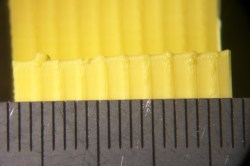

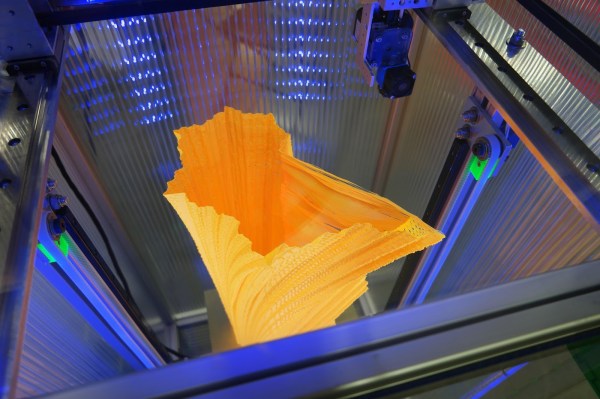

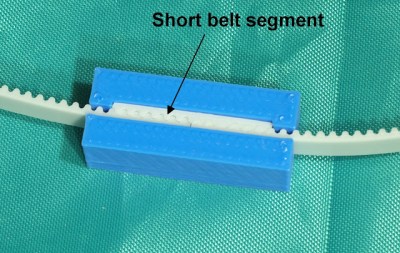

The printer is a Core XY design with four separate print heads, which are all locked together. The printer behaves as if there is a single print head which keeps it simpler than it otherwise could be. Some extra consideration needs to be paid to the print bed to ensure it’s level and flat, and it also includes a unique Z-axis designed to prevent Z-banding from poor quality leadscrews. It has a fairly wide print area, but a noticeable restriction is that it’s essentially quartered, so while it can produce many parts at once, it can’t produce a single part that uses the entire area of the print bed.

Every printed part used to make this printer was designed by [Rick] in OpenSCAD. He also built a custom electronics board with the printer drivers, and all other associated circuitry in KiCad. For anyone who prints large volumes of parts, this might be just the trick to increase output without having to manage more printers. If you already have more printers and need an easier way to manage them all, take a look at this dedicated Raspberry Pi set up to do just that.