Wireless charging is conceptually simple. Two coils form an ad hoc transformer with the primary in the charger and the secondary in the charging device. However, if you’ve ever had a wireless charging device, you know that reality can be a bit more challenging since the device must be positioned just so on the charger. Xiaomi has a multi-coil charger that can charge multiple devices and is tolerant of their positioning on the charger. How does it work? [Charger Lab] tears one apart and finds 19 coils and a lot of heat management crammed into the device.

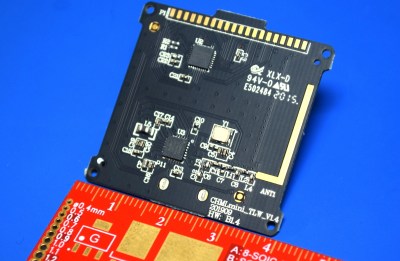

The first part of the post is a terse consumer review of the device, looking at its dimensions and features. But the second part is when the cover comes off. The graphite heat shield looks decidedly like an accidental spill of something, but we’re sure that’s just how it appears. The coils are packed in tight in three layers. We have to wonder about their mutual interactions, and we assume that only some of them are active at any given time. The teardown shows a lot of the components and even pulls datasheets on many components, but doesn’t really go into the theory of operation.

Still, this is an unusual device to see from the inside. It is impressive to see so much power and thermal management in such a tiny package. We wonder that we don’t see more wireless charging in do-it-yourself projects. We do see some, of course. Not to mention grafting a charging receiver to an existing cell phone.