Fully solar-powered handheld gadgets have so far mostly been limited to ultra-low power devices like clocks, thermometers and calculators. Anything more complicated than that will generally have a battery and some means to charge it. An entirely solar-powered video game console is surely out of reach. Or is it? As [ridoluc] shows, such a device is actually possible: the RunTinyRun gets all its power directly from the Sun.

To be fair, it’s not really a full-fledged game console. In fact it doesn’t even come close to the original Game Boy. But RunTinyRun is a portable video game with an OLED display that’s completely powered by a solar panel strapped to its back. It will run indefinitely if you’re playing outside on a sunny day, and if not, letting it charge for a minute or two should enable thirty seconds of play time.

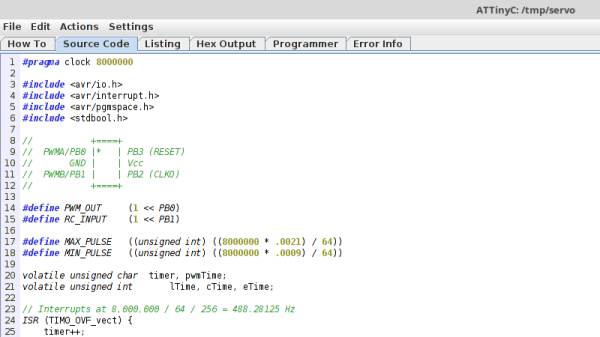

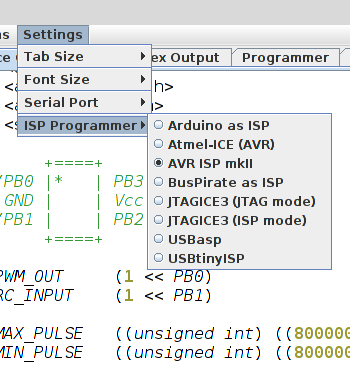

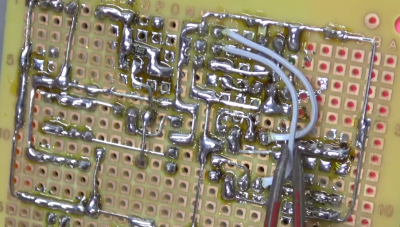

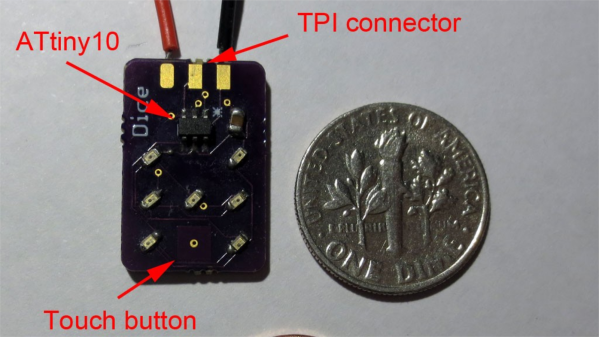

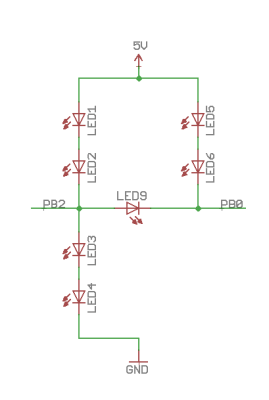

The game it runs is a clone of Google’s Dinosaur Game, where you time your button presses to make a T-Rex jump over cacti. As you might expect, the game runs on an extremely minimalist hardware platform: the main CPU is an ATtiny10 six-pin micro with just 1 kB of flash. The game is entirely written in hand-crafted assembly, and takes up a mere 780 bytes. A 0.1 farad supercap powers the whole system, and is charged by a 25 x 30 mm2 solar cell through a boost converter.

RunTinyRun is a beautiful example of systems design within strict constraints on power, code size and board area. If you’re looking for a more capable, though slightly less elegant portable gaming console, have a look at this solar-powered Game Boy.