In everyday life, the largest moving object most people are likely to encounter is probably a train. Watching a train rolling along a track, it’s hard not to be impressed with the vast amount of power needed to put what might be a mile-long string of hopper cars carrying megatons of freight into motion.

But it’s the other side of that coin — the engineering needed to keep that train under control and eventually get it to stop — that’s the subject of this gem from British Transport Films on “The Power to Stop.” On the face of it, stopping a train isn’t exactly high-technology; the technique of pressing cast-iron brake shoes against the wheels was largely unchanged in the 100 years prior to the making of this 1979 film. The interesting thing here is the discovery that the metallurgy of the iron used for brakes has a huge impact on braking efficiency and safety. And given that British Railways was going through about 3.5 million brake shoes a year at the time, anything that could make them last even a little longer could result in significant savings.

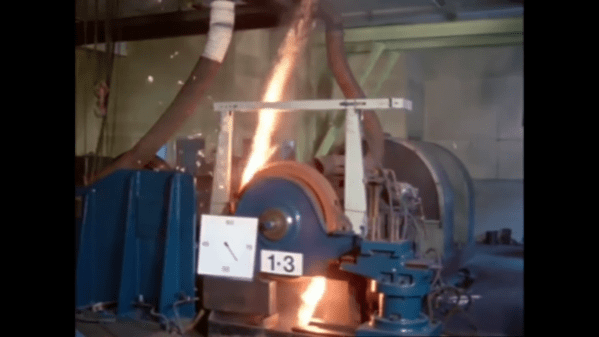

It was the safety of railway brakes, though, that led to research into how they can be improved. Noting that cast iron is brittle, prone to rapid wear, and liable to create showers of dangerous sparks, the research arm of British Railways undertook a study of the phosphorus content of the cast iron, to find the best mix for the job. They turned to an impressively energetic brake dynamometer for their tests, where it turned out that increasing the amount of the trace element greatly reduced wear and sparking while reducing braking times.

Although we’re all for safety, we have to admit that some of the rooster-tails of sparks thrown off by the low-phosphorus shoes were pretty spectacular. Still, it’s interesting to see just how much thought and effort went into optimizing something so seemingly simple. Think about that the next time you watch a train go by.